Welcome back.

Last week we looked at Jacob Rabinow—the inventor with 229 US patents—and his ideas around invention and creativity: The Jail Mentality, 606 Approach, Logarithmic Productivity, and more. If you missed it, click here to read.

Today, I want to expand on the topic of creativity with an assortment of tactics and principles. These aren’t systemized or organized. I don’t believe in a unified theory of creativity. They are simply mental models and tools for improving your ability to be creative.

Most of this is an expansion on my latest YouTube video, 7 Habits I Use for Unstoppable Creativity.

Let’s dive in.

Work with your natural grain, not against it

Anthony Trollope wrote 47 novels, 18 works of non-fiction, and dozens of other pieces over his 38-year career.

A man of extreme discipline and structure, he’d write at the same time each day (5:30am to 8:30am). Not only that, he’d have a watch on his desk to make sure he hit 250 words every 15 minutes.

Sheehan (know as The Cultural Tutor) grew from 0 -> 1.5 million followers on Twitter in 18 months as a result of his (great) writing.

Unlike Trollope, Sheehan wakes up around 4pm. He smokes a pack of cigarettes a day. He writes during the early hours of the morning when he feels compelled to do so (though, it’s worth mentioning that he writes a Twitter thread every day no matter what—so he’s still disciplined in his output).

When you look at the lives of great creatives, their habits and schedules vary widely.

Some work late at night, fueling their work through stimulants (not just coffee).

Others are spartan-like in their routines like Trollope.

Some lead extremely active social lives and would argue that doing so expands their creative ability. Others are recluse and would argue the opposite.

There is no blueprint.

That is the takeaway.

And because there is no blueprint, you should just lean into your natural way of working.

If you’re a night owl, be a night owl.

If you crave precise, daily structure—then lean into that.

And if you’re not sure what to do, then try both and see what works best.

But crucially, do not avoid doing the work.

Work diligently, every day (or as often as you can)

While the schedules and routines of great creatives vary widely, there is one habit shared among almost all of them…

They work every day (or almost every day).

No matter how they feel. No matter whether they’re tired, hungover, anxious, depressed.

When you engage in daily practice, you reap powerful benefits:

- You build momentum, and so you procrastinate less. It’s easier to sit down and do the work when you’ve done so for the past 20 days in a row. Harder when you’ve gone days or weeks without touching your craft.

- You experience insights, ideas and solutions more often. Your subconscious is attuned to the work you’re doing. It’s working for you in the background, long after you’ve finished creating for the day. Each day you work, you feed your subconscious. You give it new material. The creative person is working all the time, whether they realize it or not.

- You experience flow more often. It’s one of the best feelings in the world. A day in which you enter a flow state is a day well spent.

It’s not easy to commit to working on your craft every day, especially if you have other responsibilities, but I urge you to think seriously about how you could do so.

As David Deida writes in The Way of The Superior Man:

“As of now, spend a minimum of one hour a day doing whatever you are waiting to do until your finances are more secure, or until the children have grown and left home, or until you have finished your obligations and you feel free to do what you really want to do. Don’t wait any longer. Don’t believe in the myth of “one day when everything will be different.” Do what you love to do, what you are waiting to do, what you’ve been born to do, now.”

Follow childlike curiosity

“There’s a kind of excited curiosity that’s both the engine and the rudder of great work. It will not only drive you, but if you let it have its way, will also show you what to work on.

What are you excessively curious about — curious to a degree that would bore most other people? That’s what you’re looking for.”

Paul Graham, How to Do Great Work

To follow your curiosity, you need to:

- Suppress the analytical, judgment-centric mind. Constantly analyzing what you’re doing—or the inspiration that comes your way—is a recipe for killing momentum and curiosity. It’s over before it even starts. In other words: relax! Just work on what captures your attention without judgment.

- Tinker, experiment, be spontaneous in your work. Ask “What if?” more often. Be playful.

- Speaking of play: you should play to play, not play to win. Winning will happen. But even if it doesn’t, you’re good. Because the reward is the work itself. You win by playing the game. The infinite game.

A powerful tactic for letting your curiosity lead you is to…

Embrace redirection

Rarely do I end up creating exactly what I planned.

I start with an idea in mind. As I’m researching and brainstorming, some related (or unrelated) idea captures my attention. I curiously follow it. The end result is different to the original goal.

To me, this is what makes creativity so exciting. It’s an adventure. I don’t know where I’ll end up.

This only happens when you hold loosely your goal and vision for your work. Which isn’t always the right thing to do. Sometimes you’re clear on what it is you want to create, and deviation is distraction.

But other times, you want to embrace redirection. You want to follow the new ideas that pop up during the creative process.

You can always return to the main idea later. But chances are, you won’t. Because the new direction is far more interesting.

Work hard, disengage, then work hard again

In The Art of Thought, Graham Wallas writes about the four stages of creativity:

- Preparation: Conscious, hard, diligent work on a problem or idea. If you’re a writer, this might be researching, brainstorming, outlining.

- Incubation: The phase of creativity where you step away, disengage, and let your subconscious mind do the work.

- Illumination: The “click” – or “Eureka!” moment that one gets when the insight or solution they’re looking for penetrates their mind. Usually happens away from the work desk.

- Verification: Doing the work now that you’ve had the insight or solution. This is the endurance phase. It’s the 99% perspiration that follows from the 1% inspiration.

While this is a blurry example of what creativity looks like in practice (again, let’s not try to systemize something that shouldn’t be systemized), it is useful.

You should work hard in the beginning. It’s conscious effort.

It’s the entrepreneur trying to figure out how to take a new product to market. He’s brainstorming, studying, thinking, deliberating.

At some point, you hit a wall. Or you just feel like the idea isn’t right. Or you’re stuck and you’re not sure where to go next.

So you disengage and enter the incubation phase.

This incubation phase may last for minutes to weeks (or months, but hopefully not).

At some point, you experience the “lightbulb” moment you’ve been waiting for. The illumination. And you then enter another period of conscious effort.

A few of my own thoughts on this:

- The incubation phase is not a necessary phase. You can quite often just work all the way through. Most of my writing doesn’t go through an incubation phase. I have an idea, and I write until it’s done.

- Because the incubation phase can last for an indefinite period of time, it’s useful to be working on other projects in the meantime. This is perhaps the best argument against doing one thing at a time as a creative.

- Eureka moments can come from conscious effort too. You’re researching, brainstorming, thinking, and you come across an inspiring angle or idea that you want to pursue. These moments aren’t strictly a product of incubation.

Lower the stakes

“We tend to think that what we’re making is the most important thing in our lives and that it’s going to define us for all eternity. Consider moving forward with the more accurate point of view that it’s a small work, a beginning. The mission is to complete the project so you can move on to the next. That next one is a stepping-stone to the following work. And so it continues in productive rhythm for the entirety of your creative life.”

Rick Rubin, The Creative Act

I have nothing to add to this.

Clarity is not the starting point

Some creatives start with a precise vision in mind of what they want to create. They have extremely clarity. And it becomes a matter of just doing the work in order to realize that vision.

Others, like myself, don’t start with clarity. And that’s fine. It’s just a different way of working. I like it anyway, because it’s more of an adventure (like I mentioned earlier under Embrace redirection).

If you’re like me, then it’s helpful to remember that clarity often comes as a result of action-taking rather than through pure thought and analysis. In other words: just start.

But start wide. Explore a lot. Write down, brainstorm, research a little more than you think you need to. And once you’ve done so, a path (or multiple paths) will become clear.

For example, this newsletter is a result of a two-week deep dive into the topic of creativity, not for any particular reason—just out of curiosity. I truly believe I’ve done enough research at this point to write a small book on the topic.

I wasn’t exactly clear on what I’d create as a result of my research, I just knew I’d create something. And I’d figure that out at some point during the process.

Walk more

Advice to self.

These old school creatives and philosophers would demolish us in a daily step count competition. They walked a lot.

Maybe there’s something to it?

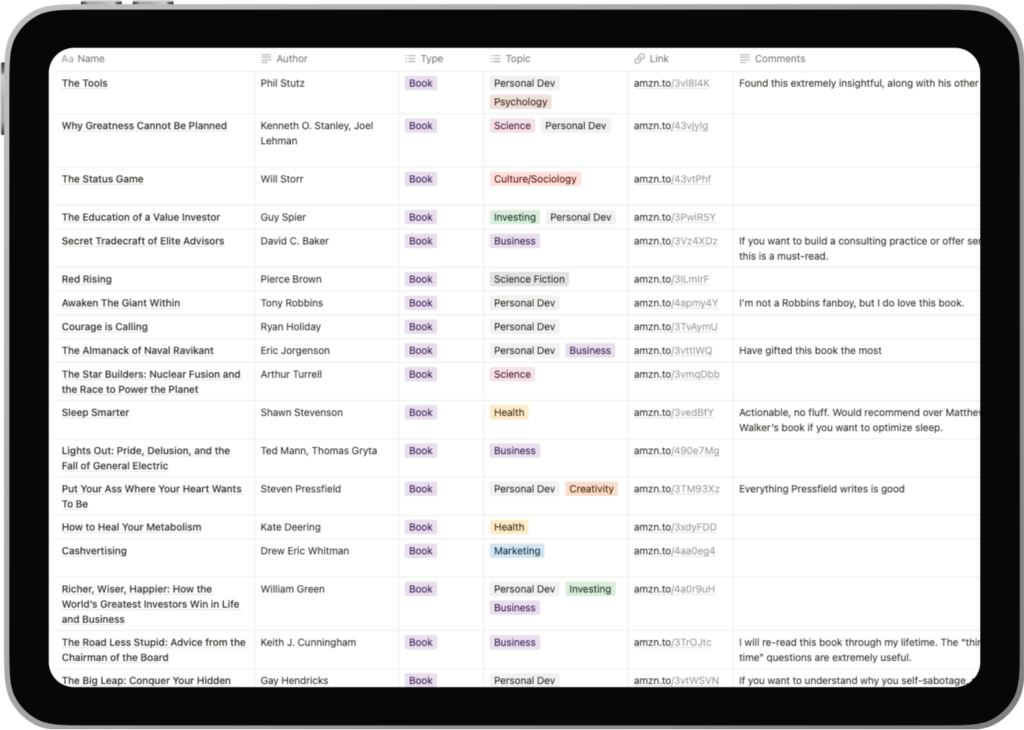

The best of what I consumed last week

- David Perell’s interview with The Cultural Tutor is one of the best long-form interviews I’ve watched in a long time. Such an interesting character, and a good example of why optimization and productivity habits are overrated.

- A Framework for Making Important Decisions by Fabrice Grinda. Worth reading. This is part 1 of 4.

- I’m working my way through Walter Isaacson’s biography on Leonardo Da Vinci. It’s been great so far.

Thanks for reading!

-Sam