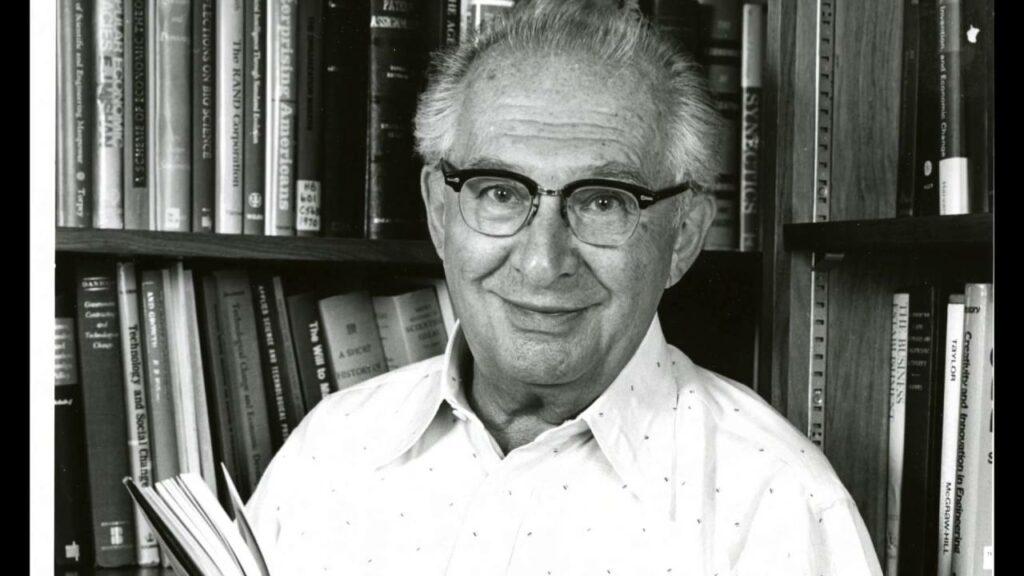

In today’s issue, we take a deep dive into the life and advice of a man you’ve (probably) never heard of: Jacob Rabinow.

You’ll discover:

- Rabinow’s “Jail Mentality” for enduring through difficult creative work

- Why you need to compete with yourself

- Why some people are 25-100x more productive than others (logarithmic productivity)

- The 606 approach: why throwing everything at the wall and seeing what sticks can be a useful strategy.

- Rabinow’s advice to aspiring inventors

Note: I talked about Rabinow on the latest episode of the Outliers podcast with my co-host Sonny Byrd. We also discuss “The Curse of Knowledge”—or why you should actively avoid learning too much as as beginner. Listen on YouTube, Spotify or Apple Podcasts.

Let’s dive in 👇

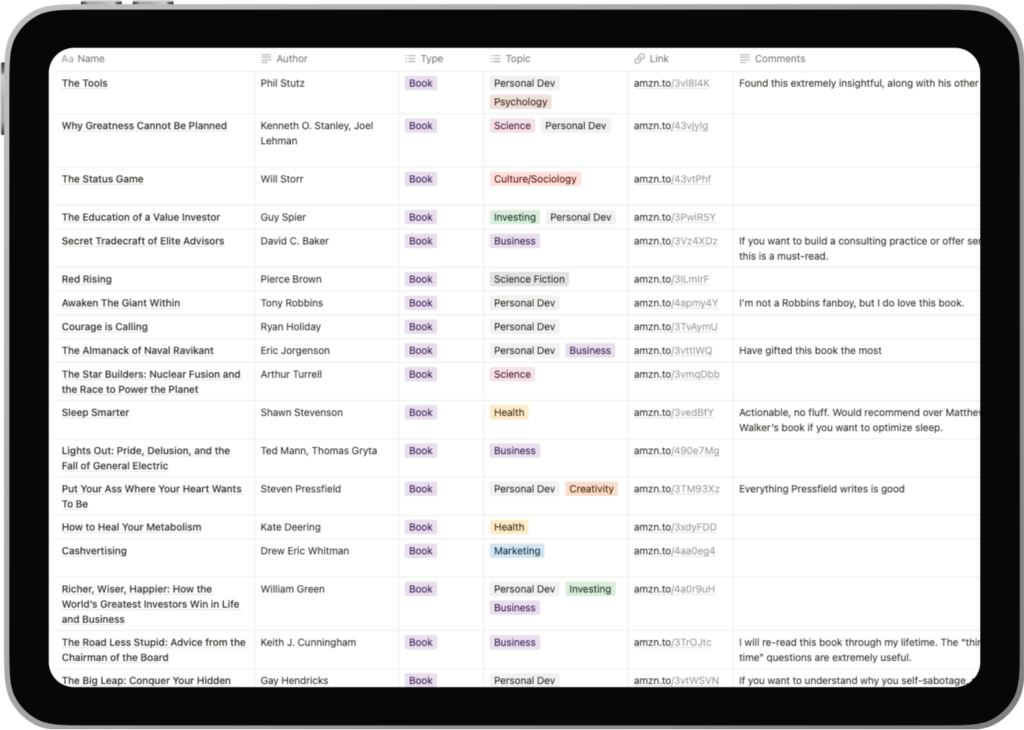

This week’s newsletter is brought to you by Rize.

Rize is a smart time tracker that improves your focus and helps you build better work habits. I’ve been using it for the past month to track all my work hours, and it’s been a game-changer for my productivity.

As a reader of my newsletter, you can get 25% off the first 3 months with promo code SAMMATLA at checkout.

Who on Earth is Jacob Rabinow?

Rabinow was a prolific inventor who earned a total of 229 US patents on a variety of mechanical, optical and electrical devices. (Including the world’s first magnetic disk memory and the automatic letter sorting machine).

Here’s the cliff notes version of his life:

- Born in Kharkiv, Ukraine in 1910. Moved to the US at age 11 after a brief stint in China.

- Graduated from City College of New York with a master’s degree in electrical engineering in 1934.

- Was hired by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Made many developments in defense systems during the war. Eventually became chief of the electro-mechanical ordnance division.

- Left in 1954 to form his own company, which he sold later to the Control Data Corporation (where he became VP).

- Returned to NIST and acted as Chief Research Engineer until retiring in 1989 (at 79 years of age!)

Rabinow was great at what he did. Great enough to break standard operating procedure and cause superiors to turn a blind eye.

As he writes in his book, Inventing for Fun and Profit:

“I was very lucky to have supervisors who knew when not to watch me too closely… as long as I didn’t do too much of this unauthorized bootleg work, I was permitted to get away with it.”

He worked on a new hand grenade design. He wasn’t authorized to do so. The money came from elsewhere in the division (proximity fuses). After the new grenade worked, the colonel in charge of the division asked Rabinow where he got the money.

“I stole it from the other projects which were very rich,” Rabinow said.

“You shouldn’t have done it,” he replied.

“If I had asked you, would you have given me the money?”

“Certainly not.”

“That’s why I didn’t ask you. Will you stop the work now?”

“No, it’s fine. We’ll give you the money; we’ll make the thing legal!

The “Jail” Mentality for Enduring Through Difficult Work

Creative work isn’t easy. Much of it is perspiration. And it’s easy to get discouraged in the process—especially when you realize how long it’s taking.

Here’s how Rabinow deals with it:

“Yeah, there’s a trick I pull for this. When I have a job to do like that, where you have to do something that takes a lot of effort, slowly, I pretend I’m in jail. Don’t laugh. And if I’m in jail, time is of no consequence. In other words, if it takes a week to cut this, it’ll take a week. What else have I got to do? I’m going to be here for twenty years. See? This is a kind of mental trick. Because otherwise you say, “My God, it’s not working,” and then you make mistakes. But the other way, you say time is of absolutely no consequence. People start saying how much will it cost me in time? If I work with somebody else it’s fifty bucks an hour, a hundred dollars an hour. Nonsense. You just forget everything except that it’s got to be built. And I have no trouble doing this. I work fast, normally. But if something will take a day gluing and then next day I glue the other side—it’ll take two days—it doesn’t bother me at all.”

Why You Need to Compete With Yourself

Creativity begets creativity.

When you come up with a brilliant idea and start working on it, you usually get a flood of other related ideas that also excite you.

Rabinow emphasises the importance of working on these related ideas. Which he calls the process of inventing “around yourself.”

“If you don’t invent a picket fence of systems to compete with your own, some other son of a bitch will. As you work you discover that there are many ways to skin the cat. That was true of my headlight dimmer, my phonograph, my reading machines, my Post Office machines, and everything I ever worked on. You end up not with one invention but with a dozen. You end up with a portfolio of patents. Your first brilliant idea was just the beginning.“

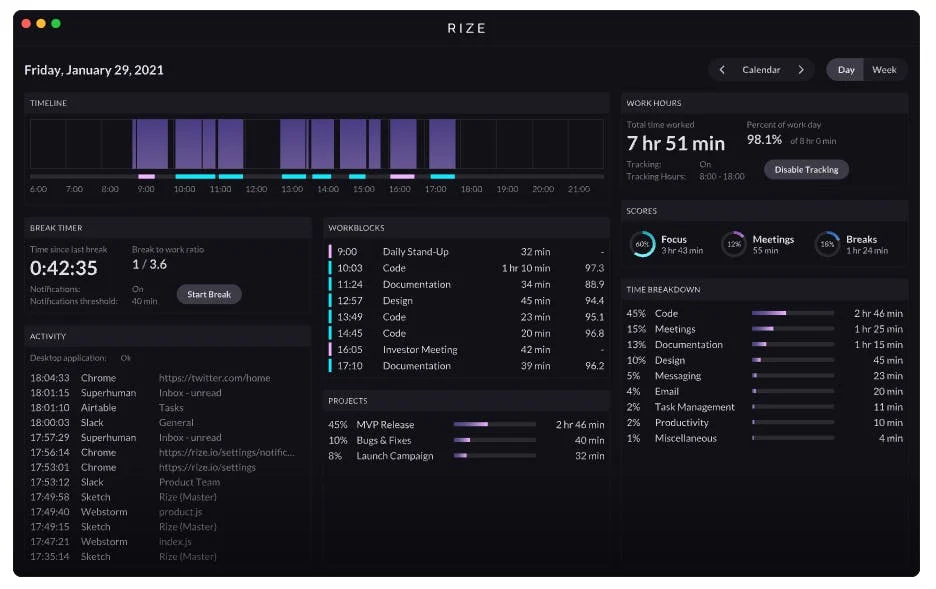

Why Some People are 25-100x More Productive Than Others

In his book, Rabinow references a paper written by William Schockley in 1957 titled On the Statistics of Individual Variations of Productivity in Research Laboratories.

Shockley notes that most of human activity varies over narrow limits.

- Pulse rates might vary between 50-100, but rates outside of a 2:1 range are extremely rare.

- Few individuals walk at speeds outside the range of 2-5 miles per hour.

- The ratio of speed for running the mile between the world record and a good high school performance is probably less than 1.5.

But when it comes to creative work, the ratios in activity and productivity can be widely different.

Shockley uses the example of idea synthesis in the field of scientific research and publishing:

The man that can only hold two ideas in his head and see the relationship between them can make the invention in two ways (1, 2) and (2, 1).

But the man that can hold these two ideas and think of another idea x, while still seeing the potential relationships between them, can synthesize in six ways: (1, 2, x), (2, 1, x), (1, x, 2), (2, x, 1), (x, 1, 2), (x, 2, 1).

Shockley implies that some people have the capacity to “hold” more ideas in their head. And that the man who can hold 3 ideas in his head has 3 times as many chances to make the invention.

He then posits another hypothesis for why some scientists are far more prolific than others:

“For example, consider the factors that may be involved in publishing a scientific paper. A partial listing, not in order of importance, might be:

1) ability to think of a good problem,

2) ability to work on it,

3) ability to recognize a worthwhile result,

4) ability to make a decision as to when to stop and write up the results,

5) ability to write adequately,

6) ability to profit constructively from criticism,

7) determination to submit the paper to a journal,

8) persistence in making changes (if necessary as a result of journal action)”

As is obvious, creative work is multi-factorial. It’s not just one kind of work.

Which means…

“If one man exceeds another by 50 per cent in each one of the eight factors, his productivity will be larger by a factor of 25. On the basis of this reasoning we see that relatively small variation of specific attributes can again produce the large variation in productivity.” — W. Shockley

This is a great mental model, the implications of which can apply to much of our modern world of knowledge work:

- Instead of trying to improve the whole of your process, consider breaking it down into individual components and improving your efficiency and ability in each.

- Identify and remove bottlenecks in your process that are slowing you down or causing friction in the movement from one step to another.

- Shore up weaknesses that are reducing your potential for a logarithmic increase in productivity.

- Figure out where you can double down on existing competencies and skills to gain a 100%+ increase in productivity in one or more steps of your process.

To give you a concrete example, here’s how I’m thinking about this with my current focus, which is YouTube.

The process involves multiple steps:

- Generating a content idea

- Brainstorming through and around that idea

- Performing research to gain depth on the ideas and sub-ideas/topics

- Structuring the research, notes and topics

- Planning out the video

- Writing the script

- Editing the script

- Filming the video

- Editing the A-Roll

- Editing the B-Roll

- Packaging the video (title, thumbnail)

Let’s say, productivity-wise, I’m at 2x the average person right now (for argument’s sake). How do I get to 5, or even 10x?

I would:

- Improve my research process and figure out how to speed it up. I’m good at it, but it takes a lot of time.

- Get a second set of eyes on each script to improve its quality.

- Hire a video editor and thumbnail designer to remove steps 9, 10 and 11 from the process enabling me to double down on the rest

And a bunch of other small improvements, but you get the idea. Minor improvements across these 11 steps can result in a massive increase in output (both quantity and quality).

The 606 Approach

Near the end of his book, Rabinow shares some techniques he uses for inventing, among which are:

- Identifying that it’s even possible to solve the problem in the first place. If someone else has done it, then it can be done. Rabinow calls it “the Russians did it” approach: “If the Russians put up a Sputnik, we can put up a Sputnik.”

- The upside-down technique: “you deliberately think of something that should be done in the opposite way from what is normally known.”

- By analogy: Rabinow writes that in the case of inventing the magnetic particle clutch: “I knew of the electrostatic effect, I knew there would be an analogous effect in magnetics, except very much stronger—and so there was.”

- The logical approach: “One logically does the thing that must be done to get the answer.” Rabinow looks down on this approach and doesn’t see it as elegant. But it can sometimes work.

But what do you do when nothing else works?

You take the 606 Approach.

He pulls this idea from Paul Ehrlich, who came across Salvarsan, the miracle drug used to treat syphilis before antibiotics.

Ehrlich’s approach was not elegant.

He tested all sorts of drugs, one after the other.

When he got to the 606th drug, it finally worked against the disease.

“That’s why I call it the 606 approach to inventing. When you can’t think of a solution, you try everything.” — J. Rabinow

Rabinow also notes that Edison used the 606 approach in developing filaments for his electric bulbs:

“He tried everything, including hundreds of plan fibers and even a hair from a visitor’s beard, to develop a carbon filament that would stay aglow in vacuum and not burn out quickly.”

Next time you feel truly stuck, adopt the 606 approach and try everything.

Advice to Aspiring Inventors

Despite Rabinow’s passion for invention and sharing his lessons, he warns budding inventors:

“My advice to inventors is contradictory. First, the best advice that I can give you is that you should realize that the risks are high, and therefore you should not spend more money on your idea or your invention than you can afford to lose. This is advice I would give to any gambler. If you decide that you want to gamble, do so. But set a limit and stick to it. Most inventors do not accept this advice. They’d say, “Yes, that makes sense, but my invention is different. It’s going to be a great success; it’s better than anything on the market today, in fact better than anything ever thought of; it’s got to go!” It is a good thing to have optimism, a necessary thing for an inventor or a pioneer. Nevertheless, the inventor is probably wrong.”

When you find yourself clouded in optimism—overly confident that what you’re pursuing will bring great success—remind yourself of the odds.

The Best of What I Consumed Last Week

- Creativity: The Psychology of Discovery and Invention – this is where I originally found out about Rabinow.

- Inventing for Fun and Profit by Jacob Rabinow. It’s on Archive.org and you have to “borrow” it each hour, but it’s worth it—especially if you enjoyed reading this newsletter and want to learn more about him. You can probably find a hardcopy somewhere if you really want.

- Solitude by Anthony Storr. Solitude is a topic I’m exploring for a new video, and this book has been a great companion during my research.

That’s it for this week! Thanks for reading.

-Sam