One weird phenomenon in life is that we chase freedom and optionality, but then it burdens us. We have too much choice. We don’t commit to anything because, well, we don’t need to—at least not urgently. While in the abstract, this freedom, this lack of pressure and urgency should feel good (and maybe it does for a short period of time), it ends up weighing on us. We feel like we’re missing something. And that’s because we are.

We’re missing urgency, action, direction, responsibility, commitment. All things that reduce our freedom and optionality, but also make us feel alive, productive, useful, powerful, important.

It’s not that freedom and optionality are bad. You should want to increase your options and potentiality. If you’re working a 9-5 that you hate, you should figure out ways to escape it and increase your freedom. Anyone who tells you otherwise doesn’t have your best interests at heart. But freedom and optionality should be used. They are resources. There’s nothing noble or impressive about going through life stacking up optionality, stacking up potential paths you could take, but never taking them. Never committing. Never putting any skin in the game.

As an aside, I must confess that I’ve done exactly this. I’ve built up optionality without exercising it, freedom without using it.

The thing is, there aren’t many—or perhaps any—good arguments against cultivating urgency and pressure in your life if you’re stuck in this position. If you’re stuck in stasis, directionless, and you have a low-level feeling of anxiety because you feel like you can do so much more.

There are very good arguments for it though, one of which I’ve just covered—which is that it makes you feel alive and useful. Let’s look at some others before we dive into how you can raise your sense of urgency.

Urgency produces great work

There’s a growing movement of people who think that your best work comes from a state of blissful carelessness and pure leisurely relaxation. That any remnants of “hustle culture” will poison your creativity. That you must actively try to be less busy and less stressed in order to do great work.

I just think this is false.

Martin Luther when he wrote his 95 theses which caused a chain reaction leading to the world we have today was not working from a state of blissful carelessness. He certainly wasn’t relaxed. He was acting with urgency.

Dostoevsky after reflecting on his death wrote with an intensity and urgency that few ever experience, and produced some of the greatest literature of all time.

Sophistication is borne out of necessity, striving, struggle, urgency.

Urgency focuses our attention. It gives us a kind of tunnel vision where we automatically filter out anything that’s not relevant to our goal or the problem we’re trying to solve. No need for decision-trees or performative productivity hacks—there’s work to do. You don’t have time to muck around.

This focused attention is what leads to better work. You’re not jumping from one half-completed project to another. You’re sitting down and sticking it out to the end. You’ve metaphorically burned the ships, you have to make it work. And when you have to make it work, you make it work and you do it well.

Urgency gives you a deep and powerful energy

As Robert Greene writes in his book The 33 Strategies of War, (from which the chapter on urgency directly inspired this video):

“When we are tired, it is often because we are bored. When no real challenge faces us, a mental and physical lethargy sets in… and lack of energy comes from a lack of challenges. Take a risk and your body and mind will respond with a rush of energy.”

If your lethargic, low-energy, and stuck in stasis, it might be because you have a vitamin deficiency or health condition. Or it might simply be that you have no challenges to produce energy for. Why hunt if you’ve already got plenty of food?

Your body wants to remain in homeostasis, but you, on a spiritual level, don’t. You crave the energy that comes from the hunt, from challenge, from discomfort, from pursuing worthwhile goals.

How to cultivate a sense of urgency

So, how do you change? How do you cultivate a sense of urgency that drives you away from mediocrity and towards greatness?

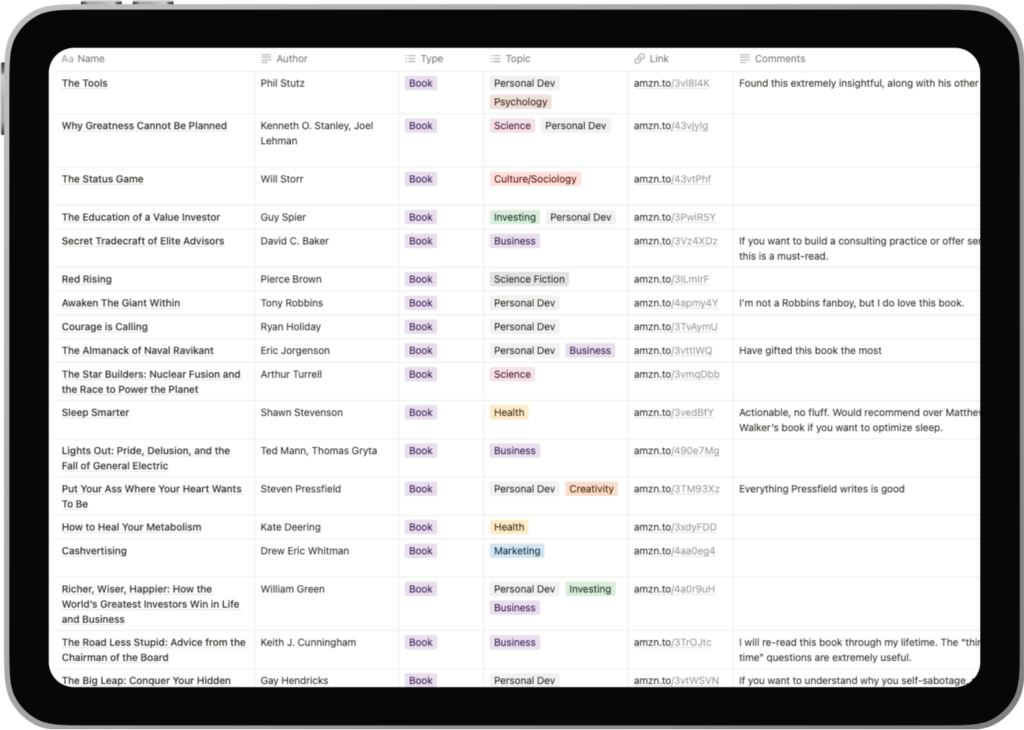

I’m going to pull a couple from Greene’s 33 Strategies of War, because his recommendations are better than mine could ever be. I recommend reading that book, particularly chapter 4 if you want to explore these ideas further.

The “no-return” tactic

This is the “burning the boats” strategy. When you don’t have an escape route, when you can’t backtrack, then you press forward with full determination and intensity.

Because you think you have options, you never involve yourself deeply enough in one thing to do it thoroughly, and you never quite get what you want. Sometimes you need to run your ships aground, burn them, and leave yourself just one option: succeed or go down. Make the burning of your ships as real as possible—get rid of your safety net. Sometimes you have to become a little desperate to get anywhere.

You must reduce your optionality, whatever that looks like. Maybe it looks like quitting your job with 6 months of runway—that’s one way to create a sense of urgency. Maybe it’s taking more risk that reduces your ability to fallback on to easier options. Maybe it’s making public commitments that, if you reversed, would have significant impact on your social status.

You might not have ships to burn, but you will have something that’s stopping you from acting with desperation.

The “death-at-your-heels” tactic

Dostoevsky, one of the greatest writers ever, was at one point condemned to death before a firing squad. Just as he was about to be killed, a messenger came—the czar had decided to let them live.

The new sentence was four years of hard labour followed by a stint in the army. He wrote to his brother that day:

“When I look back at the past and think of all the time I squandered in error and idleness, . . . then my heart bleeds. Life is a gift . . . every minute could have been an eternity of happiness! If youth only knew! Now my life will change; now I will be reborn.”

And from that day worked with a sense of urgency and intensity that few ever experience, because few ever get so close to death to be reminded of how much they’ve squandered their time.

Now, we might not have the opportunity that Dostoevsky did to be so close to death. But we can stop avoiding thinking about it. We can stop denying the reality of death. It is going to happen to us, and if meditating on it helps drive us into good, useful action, then it’s probably worth doing.

A denial of death is what leads to halfheartedness, laziness, lack of urgency and pressure. And it leads to regret.

“Society is organized to make death invisible, to keep it several steps removed. That distance may seem necessary for our comfort, but it comes with a terrible price: the illusion of limitless time, and a consequent lack of seriousness about daily life.” —Greene

Involve others

When you’re by yourself, it’s too easy to fallback into standard behaviour. No one is affected other than you—at least, that’s what you tell yourself (but in the long run, certainly other people are affected by your lack of work ethic and drive).

When you have people keeping you accountable, relying on you, expecting something from you, then you have a sense of responsibility which drives you towards action. This is why you see some men have their first child and completely shift into a new gear: they come face to face with the realization that it’s not just about them.

But you can also do this in smaller ways: collaborate on projects with others, get accountability, join something like WorkSprint and check-in every day.

Read next: