Welcome back to the newsletter! Hope you’ve had a good start to 2024.

In today’s issue:

- The white-belt mentality

- Meta-benefits as a way to increase commitment

- The best of what I consumed last week

The White-Belt Mentality

George Eastman was obsessed. Night after night, he labored in his mother’s kitchen, experimenting with different methods of developing photographs.

In 1892, he rebranded the Eastman Company to the Eastman Kodak Company. Thanks to Eastman’s relentless curiosity and obsession, Kodak soared as one of the leading companies for over a century.

Steve Sasson, another Kodak innovator, embodied this same spirit. In Kodak’s labs, he and his team birthed the world’s first digital camera, albeit with a mere 0.01-megapixel resolution. When Kodak’s executives inquired about the threat of this innovation, Sasson estimated “fifteen to twenty years.”

By 2007, Kodak was declaring bankruptcy, a stark contrast to its $28 billion market cap and 140,000 employees in 1996. The company had turned a blind eye to the digital revolution, clinging to its lucrative film business. Peter Diamandis, in his book Bold, notes that Kodak’s executives saw Sasson’s digital camera more as a toy than a transformative tool.

Kodak’s downfall is a tale of self-destruction. The pioneering spirit of Eastman had morphed into arrogance and complacency, a common trap for those who dominate their markets. This phenomenon isn’t unique to corporations; it’s a human condition we’ll call Achievement Atrophy.

You’ve worked hard. You’ve done something impressive. Maybe you’ve built a profitable business, you’re an above-average musician and everyone knows it, or you’ve published a reasonably successful book. You’re successful.

Then, the descent begins. Excellence gives way to mediocrity, innovation to stagnation, humility to arrogance. Before you know it, you’re tumbling down, unable to stop the fall – much like Kodak.

To guard against achievement atrophy, you must maintain the beginner’s mind. The white-belt mentality: curiosity, obsession, hunger, and humility.

First, remember: success isn’t eternal. Complacency can blind you to this truth. Even giants like Kodak aren’t immune to the forces of entropy and disruption. It’s better to stay vigilant against failure than to bask in transient success.

Second, realize that ego, complacency, apathy and greed eventually turn into fear, insecurity, and stress as external conditions shift. The 1996 Kodak exec was flying high. The 2007 Kodak exec was not. Two completely different states. When you feel successful is when you should feel scared, because atrophy is knocking at the door, and it leads to a dark place.

Third, understand that complacency’s consequences aren’t immediate. There’s a delay between action and outcome. Neglect and laxity don’t wreak havoc overnight; they erode foundations over time.

Day by day, you put in a little less effort. You can get away with it—or so you think. Things are going well. You do the hard things, less. You take more days off. You move from growth-focused to maintenance mode. In the short-term, nothing changes. You think you’ve cracked the code. You’re working less and you’re still doing fine!

But you’ve forgotten about input lag, and the negative compounding that’s taking place behind the curtain. Before you know it, you’re hurtling down the slope and can’t turn around. Even if you can turn around, it’s a long hike back up.

Those with a white-belt mindset can avoid this achievement atrophy. They find new ways of motivating and driving themselves, even as conditions change. They see comfort and ease as a warning sign.

They maintain a strong sense of curiosity. Even when there are long stretches of boring work to be done, they know how to reframe it in their minds to stay committed and interested.

Their response to encroaching complacency is to double-down even harder. To push. To grow. To set bigger goals. But to do so with an encompassing humility, understanding that the game is infinite and just beginning.

Meta-benefits as a way to increase commitment

“I think the majority of long-term action failures, about 60%, are commitment failures. We are plagued by doubts about whether what we are doing is what we should be doing at all.” —Venkatesh Rao, Breaking Smart

Extending your time horizon and committing to big projects is a powerful way to push your career forward.

Writing a book likely increases your luck surface area more than writing an essay. Committing to building a business over 5 years is likely to produce better outcomes than playing around with a new side hustle every 3 months.

The problem is commitment. Writing a book is hard, but half of what makes it hard is dealing with the self-doubt and the second-guessing. It’s easy to quit when you start telling yourself it’s not going to sell well and that most authors never succeed. In fact, it’s hard to even commit in the first place when you live by that narrative.

Commitment is hard. But it can be made easier by framing around “meta-benefits.”

The obvious potential benefit of writing a book is that it gets read, makes you money, builds your brand.

But there are many meta-benefits. Positive outcomes that are less tangible, but perhaps even more beneficial than the obvious extrinsic outcomes:

- By writing every day, over a long time period, you develop a level of self-discipline that few get to develo.

- The sense of accomplishment creates powerful momentum and increases your confidence, raising your internal perception of what you’re capable of.

- You learn a ton about the topic you’re writing about.

- You change fundamentally as a person by applying yourself and sticking to your commitment, even when it’s extremely tough.

When you acknowledge the meta-benefits, you can frame your commitment in a way where the downside is minimal.

You say, “Even if this doesn’t succeed commercially, I’m okay with that, because the amount of personal growth I’ll experience through working on it surpasses that which I’ll get from other projects.”

So, if you’re struggling to commit to something because you’re not sure it will succeed, consider how success would be inevitable (even if you fail on the extrinsic outcomes).

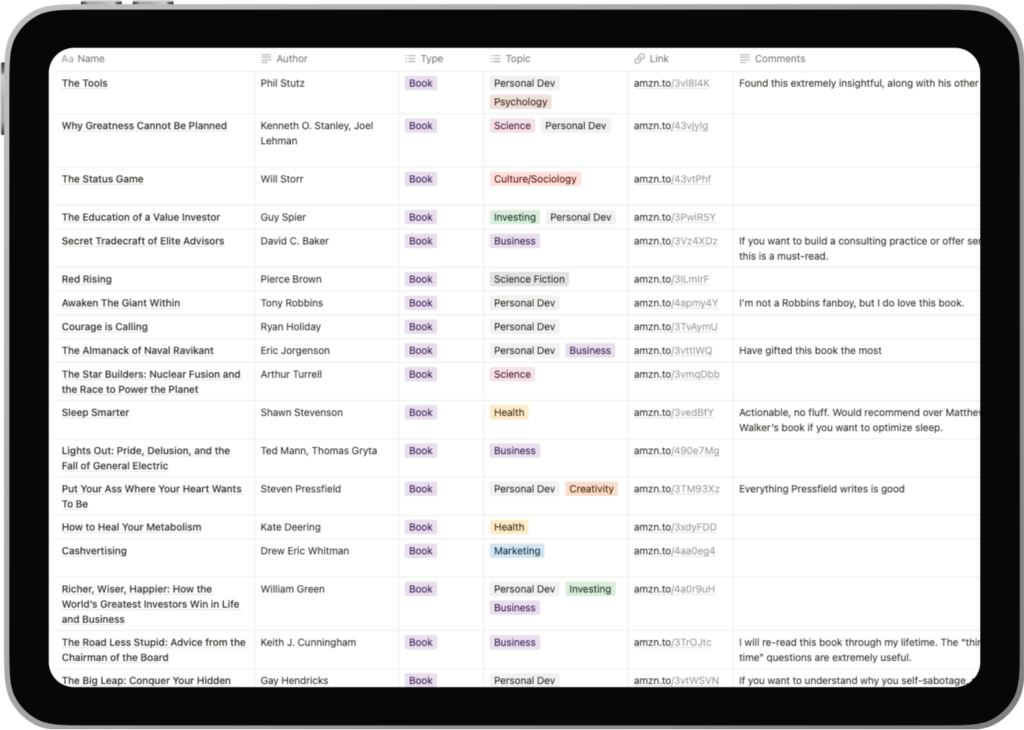

The best of what I consumed last week

- Book: Filters Against Folly. I’m halfway through re-reading this. It’s a good reminder that “everything is connected to everything else.” Systems are complex, and experts are often wrong because they fail to predict unintended consequences outside their field of view.

- Podcast: George Mack – The Game of Life. Some useful mental models in here. I particularly like the video game framing. Worth a listen.

- Book: The Daily Laws by Robert Greene. I’m a big fan of Greene and picked this up for the new year.

What about you? Come across anything interesting? Hit reply and let me know.

-Sam