If you know exactly what you want in life, this is not for you.

But if you don’t know what you want… you feel like you lack clarity, and find yourself held back by uncertainty—then keep reading.

We need to start by reframing the whole idea of “finding your purpose” or “gaining clarity.”

There’s this trap that I call The Purpose Fallacy.

You believe that if you could simply gain clarity on exactly where it is you want to go and what it is you want to do, then everything would fall into place. You would finally work hard, be disciplined, feel endless energy and motivation, and your self-doubt would disappear.

And when you believe this, you spend a lot of time thinking, theorizing, dreaming, journalling, planning… trying to capture this elusive clarity. Your life purpose. Because you think that that’s what’s holding you back.

When you suffer from The Purpose Fallacy, you falsely believe that you can think your way into true clarity and purpose.

But in 99% of cases, you can’t.

It’s hard to find your purpose by merely thinking about it

I want you to reflect on a time where you felt clarity and purpose. You were working towards something. It felt important, right, satisfying and enjoyable.

What led you to work on that thing?

Chances are, you didn’t think your way there. You didn’t spend months going around in circles theorizing and strategizing.

What likely happened is that you were working on a project, or having a conversation with someone, or reading a book, and a lightbulb went off. You had an idea, or an epiphany. Maybe you were going for a walk or driving. But prior to this lightbulb moment you were taking action on various things, you were doing, not just thinking. You were experiencing reactions to actions that you were putting out into the world. You were getting feedback that led you to a point where you had clarity—this is something we’ll come back to soon. But before that, we must understand why thinking is not enough.

There are many reasons why it’s hard to think our way towards some sort of grand purpose.

First, our desires change over time. What you wanted 5-10 years ago is likely different to what you want now. To expect your younger self to perfectly design some sort of grand purpose for your life is naive. Knowing what you want is a process of discovery, not design, and discovery requires entering the world and reacting to what it puts in your way, then introspecting on those reactions and how they made you feel.

There are a select few people who know exactly what they want from a young age, and they stick to it. But I think this is becoming less and less common in our modern age—especially as the rate of change speeds up, optionality increases, and careers become more dynamic.

The second reason it’s hard to think your way towards some sort of grand purpose is that if you’re falling into The Purpose Fallacy in the first place, it’s likely because you have optionality. An abundance of choice. If you didn’t have optionality, you wouldn’t be thinking, you’d be working to create optionality and choice.

For example, when I was 20 years old and had just gone full-time in my business, I remember doing some quick analysis of my income and expenses and realizing that I had two weeks left before I wouldn’t be able to pay rent. I was not thinking about my purpose in life. I was not thinking about how to “gain clarity.” I had extreme clarity because I had a problem staring me in the face: I needed to make some money so I could pay rent. I had very little optionality or choice. The only thing I had to figure out was how I was going to make that money. And I made that decision in minutes, because the pressure was intense.

Third, thinking requires no risk, no courage, which is what usually gives you clarity of purpose.

“Mental clarity is the child of courage, not the other way around.” —Nassim Taleb

This is exactly what The Purpose Fallacy is. You think that you will gain courage as a result of finding clarity, but actually, it’s the other way around. We often gain clarity after making commitments and following through, despite the uncertainty and risk we face.

And the final problem with thinking your way to clarity is that it’s not generative. There is no reaction to your thinking other than the inner dialogue you’re having. Sure, you can talk with people and get a reaction that way, but that’s still not really generative. You must take action to start discovering your purpose. And to understand why, we need to understand The Stasis Loop and how to escape it using the Creative Action Cycle.

The Stasis Loop vs. Evolution of Purpose & Clarity

When we’re suffering from The Purpose Fallacy, we’re spinning our wheels. We go around in circles. Perhaps we wake up one day, listen to a podcast, and have a surge of clarity. We think, “finally, this is what I need to do.”

But we don’t really act on it. Maybe we put a few hours into the new project or goal, but we wake up the next day and tell ourselves that the new path isn’t the right path, and that we need to go back to the drawing board. And so we repeat the cycle.

This is called The Stasis Loop, or the “Inaction” loop. You could call it the comfort zone, but as you already know, the comfort zone gets very uncomfortable very quickly. Because it’s an uncomfortable thing to know that you have potential that you’re not actively working towards. There’s a gap between who you know you can be and who you are today, and it’s vast, and your behaviors are not getting you any closer. One of those behaviors is going around in circles hoping to come across some supreme clarity.

But the purpose and clarity you seek exist outside of this loop. Outside the loop are multiple paths. These paths are the beginnings of clarity and purpose, and you want to venture down them and see where they lead. But you can’t do that until you exit the stasis loop and enter the world of action and consequence.

Once you do exit the loop, you can start venturing down these paths. Initially, you might not even be on a path. It might feel like walking through thick forest. But eventually, through taking action, you’ll find a path—and it will excite you, and you’ll start going down it.

Of course, there will be doubts. You might backtrack. You might feel the gravitational pull of the stasis loop. But you’ll continue on. And as you continue down the path, taking action, you’ll be presented with deviations, offshoots, and forks in the path.

As you make decisions and progress, your sense of purpose and clarity will evolve. What seemed like a random path in the beginning is now much clearer. Perhaps you can see an objective near the end, but more importantly, you can see how traveling along the path is changing who you are. You think back to your time stuck in the Stasis Loop and know that you never want to go back there, as alluring as it may seem at times.

Escaping the Stasis Loop with The Creative Action Cycle

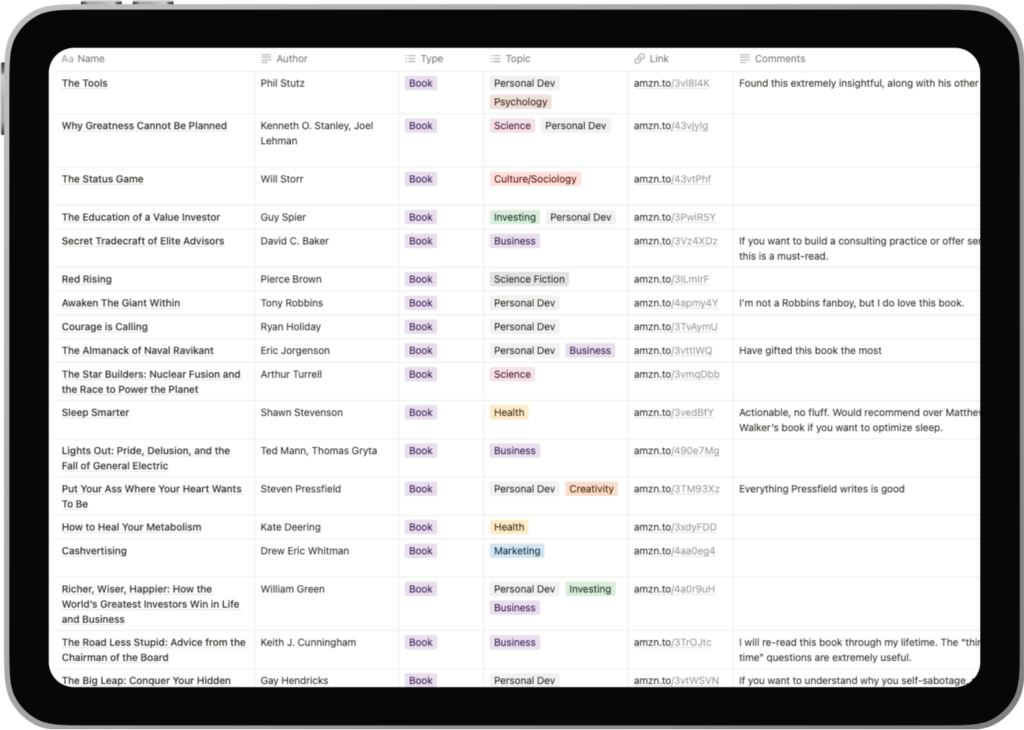

Phil Stutz, the famous therapist, talks about this cycle he calls The Creative Action Cycle.

It involves three main components: instinct, action, and consequence.

You have an instinct. You act on that instinct. You get some sort of consequence, a reaction to your action. It might be good, or it might be bad. If it’s not what you want, then you perform a correction, and then repeat the cycle.

Instinct and action are what pull you out of the stasis loop. Instinct is the antithesis to circular, unproductive overthinking. You must train yourself to take action on it, because it’s a genuine signal.

I’m not saying you should act on every instinct. Some instincts are obviously bad, and you know what those are. I’m talking about positive instincts.

Perhaps you feel an impulse to make a YouTube video on a topic you’ve been reading about. Your tendency in the past has been to suppress that instinct because it requires you to take action and do work, which is uncomfortable. But this is a positive impulse. And unless you already know exactly what your purpose is and you’re working towards it and can confidently say that making that video is a distraction from your primary goal, then why not act on it? The alternative is ruminating and continuing to swim around in the stasis loop.

So you take action on the positive instinct. You start writing the script for your video. And you experience a consequence. That consequence might be that you’re really getting in the zone. You’re enjoying the process. You’re experiencing a flow state for the first time in months. And that consequence produces a new instinct, which is that you feel you should probably continue to write the script, because it’s enjoyable and it feels satisfying—even if it’s hard and frustrating at times.

At some point, you finalize the video and it’s ready to publish, which introduces you to a new consequence: maybe you feel fear. You don’t want to publish. You take courage and do it anyway, which introduces a new set of consequences: maybe no one watches it and it floats in the ether of the internet. In which case you can either be discouraged and quit, or simply view it as part of the process and continue on. Or maybe it goes viral, and you get a ton of subscribers, and your life changes. You simply don’t know what can or will happen until you work your way repeatedly through the Creative Action Cycle.

As Stutz writes in his book, “Each consequence leads to a new instinct, which starts the cycle again… The truly successful person has the courage to work this cycle over and over again.”

It’s important to note that instinct doesn’t mean “good feelings.” That voice in your head that tells you “You should probably make a second video” might not feel good after the first one gets no views, but it’s probably a good instinct. Instinct doesn’t need to be a deep, powerful feeling. It can be a small impulse. A “should”, or a “let’s give it a go.”

You use this cycle to escape the stasis loop, and then you continue cycling through it as you travel down paths. It is the engine by which you transport yourself along toward clarity and purpose.

Fully Engage With Forward Motion

In some sense, you already have a purpose: it is to evolve, to be in forward motion.

And maybe you argue against this. Maybe you say, “Well why can’t I just relax and enjoy life?”

You can. But at some point, if you’re like most people, you’ll feel something’s missing. We are designed for growth and challenge.

When you reframe your purpose as to simply be in forward motion, it simplifies things. You become more agnostic about what you’re doing, at least for a time. You check off tasks, you increase your productivity, you get things done, you feel a lot more confident and alive. This opens up a world of possibilities. The feeling is almost unparalleled.

To give you an example: for many years I avoided taking sales calls in my business ventures. I told myself that I didn’t like having things on my calendar (which was true) and that I needed to keep it clear so I could focus on the work that was more important (which was a cope). Ultimately, I wasn’t practiced at sales calls and found them uncomfortable—like everyone does when they first start.

I’d constructed a convenient narrative, which was that I was “above” sales calls—and my leverage came from my writing and creative abilities instead. But eventually, I realized that I was just avoiding learning a new skill that would make me a better entrepreneur purely out of discomfort avoidance—so I forced myself into a position where I had to take sales calls. I sent an email out to my list, opened up coaching spots, and had people book calls.

The difference this time is the framing that I was taking. I knew it was going to be uncomfortable, but I also knew it was forward motion. And it would be useful in some way to do this, even if I completely failed. I was right. The process was expansive. I think after the 5th call I did, I felt a powerful sense of mental expansion. It’s almost like an entirely new world opened up to me. I realized I could actually do sales calls, and I even enjoyed aspects of them.

Don’t know where to start? Solve the problems in front of you

“your diamond is not between the distant mountains and the sea, if you are determined to dig, the diamond is in your backyard.” — John D. Rockefeller

The Purpose Fallacy makes you think that all your problems will be solved if you simply figure out your purpose, but in fact it’s the other way around: as you solve the problems in front of you, you build momentum. You gain clarity. You feel better. You develop discipline and good habits. You discover what it is you really want, and you also have the energy and drive to move towards it in a way that you didn’t when you were facing other problems.

In a way, it’s Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. You don’t get to play with self-actualization until you’ve solved more fundamental problems.

In a practical sense, this principle should bring you face to face with your reality, as painful as that might be.

You might think, “I don’t know what goals to set.”

But if you’re unhealthy, overweight, not exercising, and not eating well—then you have a problem to solve. You already have an incredibly important goal to achieve. You say: “Let me focus on getting healthy, then I can worry about what my life purpose is.”

Or if, like I did, you need to make money: then that’s a problem to solve. It’s hard to get clear on your life purpose when you’re stressed out by money or poor health. These are fundamental problems that need to be solved.

Stop thinking that you need certainty in order to act

You are a more powerful person if you can learn to live with uncertainty and discomfort than try to eliminate it. It is likely always going to be there in some form or fashion.

You will not arrive at a point in life where you have complete certainty or clarity, because even if you have it in one domain—like your work—it A) won’t last, because your work, career, business is dynamic—and B) there are other domains in life like family, health, personal pursuits that contain their own uncertainty and decisions to be made.

21 days of aggressive, consistent action in some direction

We’re going to shorten our time horizon. Forget the long term goals, forget the big picture, and just focus on one thing for the next 21 days. Our goal here is to get ourselves into a state of forward motion, doing things, putting them out into the world so we can get real data and signal that guides us toward purpose.

Here’s how you can do this.

First, think of all the things you could do with your life. All the possible purposes. This is the only time during this process you get to think about the long-term goals and big picture.

Maybe you want to be a writer, but also an entrepreneur, but also an athlete. Write all these down. Everything that comes to mind. Everything you ponder and think about.

Next, write down what a 21-day measurable project could be, for each. If you want to be a writer, then this could simple be 21 days of writing with the aim to publish something at the end. If you want to be an entrepreneur, it could be 21 days of cold outreach to potential customers. Figure out a basic action, or set of actions you can do repeatedly for 21 days.

Once you’ve done this, choose the one that most appeals to you. It’s at this moment that the overthinking brain might spark up, but you must remember two things:

- It’s only 21 days. If you make the wrong decision, it’s fine.

- Making a decision will move you closer to your goal of figuring out what it is you want to do than more thinking will.

If there isn’t a particular one that appeals to you, or they’re all equally appealing, then just choose one. You can do the others later if you want.

Next, you want to do the following:

- Write out the exact tasks and work that needs to be done. It might be writing for an hour per day without distraction. Write that down.

- Write out what you won’t do during the 21 days. You might have to sacrifice something. For me, it’s usually the distracting side projects that pull me away from what I should be doing and stop me from building momentum. Write down on paper, “I will say NO to doing X, Y and Z”

Have a one-pager. A clear plan.

Every morning, remind yourself of your 21-day goal. Write it down—pen and paper ideally. Drill it into your head.

And then stick to it. Do not quit. When you feel like quitting, remind yourself that the character traits you build by enduring and following through are valuable, rare, and extremely powerful.

Perhaps you think you’re above just focusing on something for two weeks. You’ve done bigger things in the past. You’re looking for the thing to really sink your teeth into. But you’re not above this. The purpose of working on, and finishing a project over two weeks is not to simply finish the project. It’s not about whether the project succeeds or not. The main purpose of this activity is to give yourself a new data point that gets you closer to clarity.

Read next: How to be ULTRA Productive With The SPRINT Method