Hey!

Another issue of the Work Notes newsletter to kick off May.

This week, we’ll look at:

- 3 mental models for productivity, performance and decision making

- The life-changing habit of micro-commitments

- The best content I consumed in April (books, articles & podcasts)

Read time: ~15 minutes

3 Mental Models for Productivity, Performance & Decision Making

Mental models are tools for making better decisions.

In the world of productivity and high performance, decisions matter.

If you’re not aware of your blind spots and biases, then you’re likely to make a poor decision—ending up on a path that is a complete waste of time. Or worse, destructive.

Consider the person who’s extremely “productive” in the sense that they can sit down and focus for hours on end without distraction…

…but they’re working on something that doesn’t make sense.

It doesn’t fit their skillset or inclinations.

It has an extremely low chance of success.

It’s driven purely by their ego.

At some point along the way, this person made the poor decision to pursue this less-than-ideal path. And all their productive energy is being pushed towards it.

But if you improve your ability to think and make good decisions, then you’re far more likely to end up in the right vehicle. The productive energy and focused effort you do apply will end up getting you better results.

That’s why Naval says things like:

“Decision-making is everything. In fact, someone who makes decisions right 80 percent of the time instead of 70 percent of the time will be valued and compensated in the market hundreds of times more.”

And…

“If you can be right and more rational, you’re going to get nonlinear returns in your life.”

With that context, let’s look at three mental models that can help you with productivity and decision-making: Circle of Competence, First-Principles Thinking, and Inversion.

Circle of Competence

A quick way to kill your productive output and performance is to take on a project or pursue a goal that is well outside of your circle of competence.

And that’s the best-case scenario. The worst is that you are productive and pursue it anyway, only for it to end in catastrophic failure. History is littered with examples of egotistical, previously successful people who ventured too far outside their circle of competence, and paid the price for doing so.

But usually when you take on something outside your circle, it’s overwhelming. You find ways to avoid the work. It’s confusing. It’s too hard. It’s discouraging. It kills your productivity.

Don’t misunderstand this mental model. It’s not that you should always do what you know how to do and never challenge yourself. You need some degree of challenge if you want to get into flow states, which most of us do.

It simply means that you shouldn’t jump too far outside your circle of competence out of overconfidence.

One way to think about this: you cannot jump into another circle of competence or instantly acquire a new skill. You need to absorb it using your existing circle.

The only way you can do this is by expanding and pushing the edges of yours (growing it big enough) until you get close enough to absorb it.

And the most efficient way to do this is by expanding your circle to absorb new competencies that are already close by.

For example: my circle of competency includes skills like writing, content creation, information synthesis, marketing and psychology.

It’s extremely difficult (and likely a poor use of my time) to jump all the way over to advanced theoretical physics, or industrial engineering and design. I know next to nothing about these fields, and there isn’t much in my existing circle that I can leverage.

But there are some closer-by skills that I can more easily absorb by expanding my circle of competence, if I wanted to. Skills like fiction writing, storytelling, filmmaking, and others.

Note: “absorbing” skills is an incomplete illustration because it implies that skill acquisition is binary. It’s not. It’s a slow process that happens over time. You should think of your circle of competency as always expanding and always absorbing (assuming you’re working towards doing that). It’s an ever-evolving blob that looks nothing like a circle in reality.

But how does this apply to productivity & decision making?

As a mental model, the idea of your circle of competence should influence the projects and goals you decide on.

Ideally, you are doing challenging work that leverages your existing circle of competence (you are suited for it), but also deepens and/or expands your circle (you’re forced to learn new skills/fields or improve existing ones).

When you find yourself thinking of highly ambitious projects or goals that don’t leverage your existing skills or competencies at all, you should be wary that you’re not falling into trappings of ego and delusion.

I know there’ll be pushback against this point, but for every entrepreneur and highly ambitious person who’s “done the impossible and proven everyone wrong.” There are 100 others who have failed, because they ventured way too far outside their circle.

It’s not defeatist. It’s not anti-ambition. It’s rational.

First-Principles Thinking

Most of the time we make decisions based on a messy combination of mimetic desire (mimicking other people and what they do—thinking it’s the best thing for us), ego, desire for status, and previous experience.

A better approach—especially with big decisions—is to start with what’s true.

Say you’ve got a business idea that you’re interested in, but you also have a decent career that pays well and is enjoyable. You’re torn. You want to start the business, but there’s also a clear path to promotion in your job.

You have a bunch of assumptions about each choice.

- Starting a business = high risk. Might fail. Stressful. Long hours. etc.

- Pursuing career = less autonomy. Earning cap. Might regret not starting business. Lower status.

And some of these assumptions might be true. But you should really delve into the first principles. The fundamental truths.

For example, is it actually high risk to start a business? Well, that depends on:

- What type of business it is

- The market

- The competencies of the founder

- Many other variables

If the business idea is a high-growth startup that requires venture capital, there’s a huge risk of failure compared to if the business idea is a home services business in a high-demand market. The latter is much harder to screw up.

Is it inherently stressful to run a business? Well, maybe. But first principles thinking might show you that it’s not inherent or necessary, you just have to design your work and your business to mitigate stress.

The point here is that you need to dig deeper and keep asking, “Is this true? Or is it just an assumption? How can I find the facts?”

But be warned, this can easily become an analysis paralysis loop if you’re not careful. First principles thinking can help you get closer to the truth, but it won’t necessarily give you absolute certainty. At some point, you will still need to take courage and make the decision—but hopefully with more clarity and confidence knowing that you’ve done the thinking work.

Inversion

Avoiding stupidity is easier than seeking brilliance.

Inversion is a powerful and underrated mental model, especially once you practice it and it becomes an intuitive part of your decision making.

As Shane Parrish writes in The Great Mental Models Vol 1, there are two approaches to inversion:

- Start by assuming that what you’re trying to prove is either true or false, then show what else would have to be true.

- Instead of aiming directly for your goal, think deeply about what you want to avoid and then see what options are left over.

The second approach is highly useful for productivity and decision making.

The default way of planning and thinking is to aim towards what you think is the best outcome. But sometimes the easiest way to find the best outcome is to first consider the worst outcome.

Let’s say you want to design the ideal daily routine, but you’re having trouble figuring it out.

Use inversion to think about the worst possible daily routine. What happens in the day? What bad habits are exercised?

For example, it might go something like:

- Sleep in, wake up late. Already behind on the day and feel rushed.

- Slept poorly the night before. Craving carbs. Eat sugary breakfast.

- Haven’t planned out day. Spend 3 hours procrastinating before getting to first task.

- Highly distracted. Can’t focus on work. Lunchtime. Craving bad food again. Crash after having huge meal.

- Afternoon is worse than the morning – zero productivity.

- Haven’t moved much at all today. Feel like a slob and a failure. Numb this feeling through mindless entertainment.

- Mindless entertainment continues into the evening. Get poor sleep. Repeat again the next day.

Obviously you can have worse days than this (you could end up in a car crash for example), but we are talking about routines here—and this is an unfortunately common example of a bad daily routine.

But now we can apply inversion.

- Have an optimal evening routine that forces winding-down, no screens, stop eating before 7pm to ensure a great sleep. This means I won’t sleep in. I’ll get up when I need to get up and have a head start on the day feeling rested.

- I skip breakfast, or have a healthy breakfast that gives me energy instead of causing me to crash.

- My day is planned out the night before. I focus on the most important task and have systems in place to prevent procrastination.

- After my healthy lunch, I go for a 30-min walk prior to lunch to get fresh air and move my body. This also helps prevent the afternoon crash.

- Finish work, hit the gym. When I exercise I sleep better, and I’m less likely to watch mindless entertainment in the evening because I feel tired and want an early night.

This is one example. You can apply inversion to practically everything:

- What’s the worst business or project idea you could work on?

- What’s the worst city or country you could live in?

- Who’s the worst type of person you could enter a relationship with?

The life-changing habit of micro-commitments

When we think of the word “commitment”, we often think of big commitments.

Marriage. Partnership. Big goals. Decisive action towards a long-term project.

But commitment requires tolerance.

Tolerance of both pain and boredom.

And you can train this tolerance every day with micro-commitments.

Really, it’s just doing what you said you were going to do. Not just some of what you said you were going to do, but all of it.

This is a mindset shift that I’ve been making over the past month. I’ve found it too easy in the past to rationalize half-hearted attempts at fulfilling a commitment, and I’m changing that.

For example, at the gym: I’ve found it easy to skip the last set or last exercise. The rationalization is that “I’ve already spend 40 mins here and I’ve done 95% of what I need to do, so the last set doesn’t really matter.”

Oh but it does matter. Because I said I was going to follow this routine. And if I skip that last set then I’m breaking my commitment.

So now when I’m working out, whether it’s lifting or cardio, I go all the way. I do the last set regardless of whether I feel like it or not. I push through the boredom and the pain.

If I tell myself I’ll do 3 hours of deep work today, then I’m not going to stop at 2 hours 50 min. I’m going to go all the way.

Old Sam would have laughed at this, because what’s the functional difference between doing 2:50 of deep work vs 3 hours? There really isn’t one.

But the difference in output is not the point. Whether you do the last set at the gym or not doesn’t have that much impact on results.

The point is that you become the person who does what they say they are going to do, and doesn’t take shortcuts. Because it compounds. Taking a shortcut once makes it easier to take one again. And fulfilling a commitment, all the way, especially when you don’t want to because it’s boring or painful… this also compounds, and makes it easier to do next time.

There’s a phrase I keep telling myself when I feel like taking a shortcut or not fully completing something:

“I said I was going to do this, so I’m going to do it. That’s who I am. There is no alternative.”

Sounds cheesy. But try it next time you feel like quitting early.

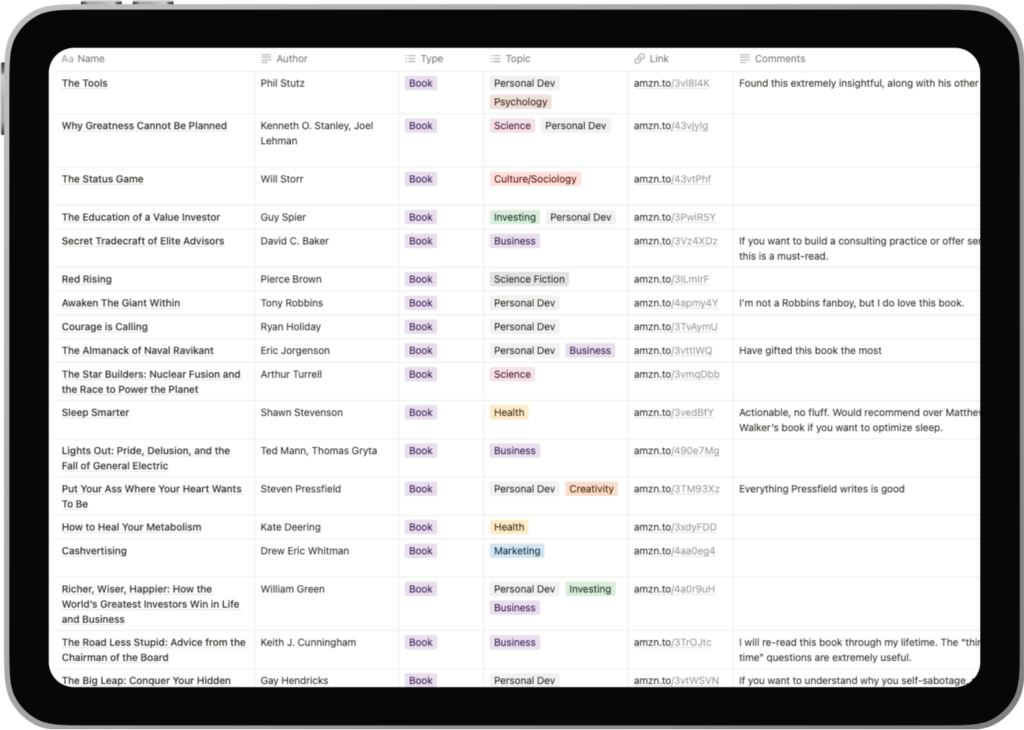

The best content I consumed in April

I intentionally ramped up my content consumption in April for two reasons:

- I’ve noticed that the periods in my life where I’m reading and consuming a lot are generally extremely productive periods. More inputs = more creativity and output.

- I’ve been doing a bunch of zone 2 aerobic exercise (incline treadmill walks) per Peter Attia’s recommendation. It’s been a game changer. But it’s boring. So I listen to a lot more podcasts.

On that last point, I have a new iron rule which is that I only listen to long-form podcasts or content while moving.

Anyway, here’s the best of what I consumed last month:

Books:

- The Art of Living by Epictetus

- Caesar: Life of a Colossus

- Endure by Alex Hutchinson

Articles:

Podcasts/Videos