There’s this idea in self-help books that you can do anything you want or be anyone you want.

It’s false. And it’s not the right way to think about it, anyway.

No matter how much effort I put in or how good my coach is, I will never be an elite marathoner like Eliud Kipchoge. I don’t have elite Kenyan running genes. In fact I don’t have good running genes at all.

Neither will I win a Nobel Prize for physics. My ability to think in the abstract is good, but not excellent. Jeff Bezos recognized a similar limitation in himself.

These are not “limiting beliefs.” They are facts.

I’d much rather pursue goals that align with my nature. To do what I can do best, instead of falling victim to delusion and visions of grandeur.

But what does it mean to lean into your nature?

And what if you don’t know what your nature is? How do you find it?

Let’s explore.

Limiting beliefs vs. surrendering to your nature

The self-help guru will say that surrendering to one’s nature is to limit oneself. That you are capable of more than you think. You can adapt, you can grow, your nature is changeable.

To some extent, they are right. The advice to aggressively remove limiting beliefs from your mentality is good advice. Too many people place artificial limits on themselves, and are capable of much more than they think they are.

Surrendering to your nature does not mean accepting limiting beliefs. If anything, surrendering to your nature will take you further than you ever thought possible.

It’s more limiting to act against your nature than to surrender to it. When you act against your nature, you are like Sisyphus, constantly pushing the boulder up the hill. You live a life of unnecessary strain. Instead of healthy discomfort, you feel horrendously out of place. Mismatched.

Still, you want to make sure that you’re leaning into your nature and not leaning into the comfort that limiting beliefs produce.

Limiting beliefs vs. truths

It’s important to distinguish between useful beliefs that are based on probable truths, and help us better understand who we are, and limiting beliefs that hinder us.

Years ago, I often used to tell people, “I’d never be able to build a big business like those other guys do. Having dozens of employees would stress me out.”

This limiting belief was based on… well, nothing. Just a preconceived notion that having lots of employees would stress me out. Which it might. But to say, “I’d never be able to…” is bad language.

This belief was shattered when a friend challenged me on it by asking, “But why would it be stressful? You’ve never experienced it so how do you know. Also, who says stress is a bad thing? Maybe it’s worth it.”

I realized that I held this limiting belief largely to maintain mental comfort. If I told myself the story that building a big business was too stressful, then I wouldn’t need to consider that as a goal. I could remain where I was.

Then we have facts. Truths.

Here’s one for you: “I have zero experience managing a company of 100 people.”

This is objectively true. I can either choose to let this fact limit me by saying “because I have no experience, I shouldn’t do it.” Or I can simply treat it for what it is—a fact—and use it to keep me humble and hungry. If I know I lack experience, then I can avoid the trappings of overconfidence and ego.

Removing limiting beliefs expands your scope of opportunity

Switching from the belief, “I’d never be able to build a big company because it’s stressful…” to the fact “I have no experience building a big company, so I’m not sure if I can do it or not, but I could absolutely give it a good shot” changes things. It opens me up to a wider pool of potential goals and opportunities, because I’m not automatically eliminating them based on my limiting belief.

But expanding your scope of opportunity leads to its other problems. The biggest being, “Okay, so which opportunity do I pursue?”

Just because something is possible, it doesn’t mean it’s wise. Just because you can pursue an opportunity, it doesn’t mean you should. And so, after expanding our scope, we must then reduce it by asking ourselves which opportunity (or opportunities) make sense in light of our nature.

Surrendering to your nature reduces your scope of opportunity

But it increases the depth and rewards that come from the opportunities.

When you surrender to your nature, you cut yourself off from options. You firmly say, “I’m way more X than I am Y. And therefore I’m much better off pursuing Z instead of all the other options.”

You’re sacrificing optionality. But that’s a good thing. Because optionality is overrated anyway.

It does, however, feel painful to reduce your scope of opportunity. It feels painful to surrender to your nature. Because you need to accept that you can’t just be anyone or anything. You need to accept that some opportunities are not right for you, as prestigious and exciting as they may seem.

But it’s a good pain. A necessary pain. A pain that leads to immense personal growth.

The person whose nature it is to be a writer, and who surrenders to that nature, stops swimming in the sea of open options. They stop diffusing their ambition and focus. They say “It’s in my nature to write, and so that’s what I’m going to do.” Is it easy for them to do this? No. It’s painful. But it’s commitment. And it’s the path that must be followed to do great work.

How to figure out what your nature is

What if you don’t know what your nature is? How do you find it?

It’s more a process than it is an event. But there are practical things you can do to speed up the process.

Experiment. A lot.

If you have no idea what your nature is, then you need to experiment. You need to try a lot of different types of work to figure out what you like and don’t like.

Take note of the types of work that get you into a state of flow and make you feel immense satisfaction. Take note of the work that feels like play.

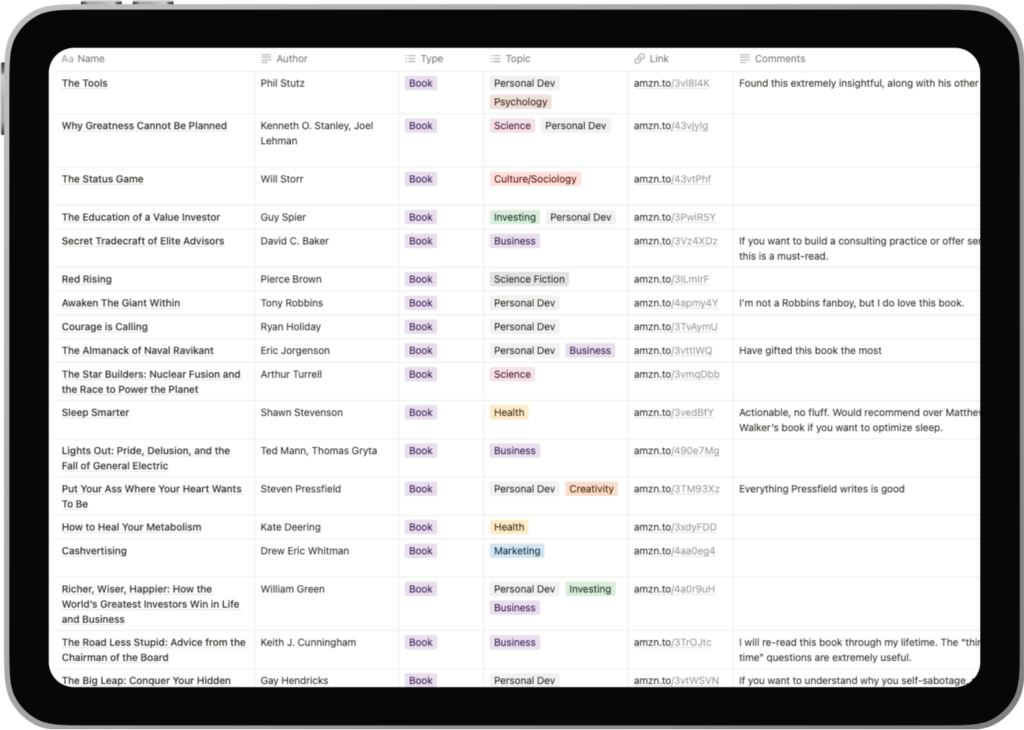

Gain vs. Drain

Get a piece of paper, draw a line down the middle, and in one column put the header “Gain” and the other “Drain”

Then, think back over the last week or two. What did you do that caused you to gain energy? What made you feel more alive? What made you feel good? Write those tasks/activities down in the Gain column.

Next, repeat for the Drain. Which activities drained you? Which tasks did you dread?

Don’t limit yourself to the past week or two either. If there’s tasks you know that cause you to gain or drain energy that you’ve done in the past, write ‘em in.

This seems like a simple exercise, and it is, but it forces you to confront the reality of things.

For example, the first time I did this, my columns looked something like this:

- Gain

- Writing

- Deep work & flow states

- Research

- Reading

- Sun exposure

- Lifting

- Running

- Eating steak

- Good conversation with friends

- Spending time with my wife

- Strategizing

- Building products

- Drain

- More than 2 zoom calls per day

- Client work that I shouldn’t have taken on

- Alcohol

- Administrative tasks

- Creating processes and SOPs

- Having too many surface-level conversations

- Things that reduce my sense of autonomy

The purpose of this exercise is not to stop doing all drain activities (though, you should stop doing those that can be stopped). Rather, you should focus on the gain activities. The things that energize you most are likely those that align most with your nature.

Introspect: What did you do as a child?

Robert Greene, in his book Mastery talks about how what you did as a kid is most likely your calling.

No, that doesn’t mean you should be playing Runescape as your job just because you played it as a kid. But if you loved Runescape then it probably tells you something about yourself.

If you were the child who stayed inside reading lots of books, then that tells you something about your nature.

If you were the child who was always playing outside, trying to build structures and tear them down, then that tells you something about your nature.

If you were the child who was extremely social, always wanted to play, and didn’t like being alone, then that tells you something about your nature.

If they’re still around, ask your parents what you were like. They may provide insight that you can’t.

As a child, I was always trying to figure out how things worked. I’d take apart electronic devices. I had no idea what anything did, but I liked trying to figure it out anyway. I also liked building structures and things outside. I’d pretend I was playing Age of Empires in my backyard. I also liked writing.

And when I look at the work I’m doing now, it incorporates these elements. My days and weeks consist of a lot of research, really trying to drill down on how things work (specifically in the domain of human performance and development). Synthesizing that information to create something new. Building a business in the process. And using writing as the foundational activity to drive all of it.

—

Beware of engaging in narrative fallacy here. It’s easy to draw connections that don’t exist in order to rationalize where you’re at right now. If you’re in the wrong career or job, but it’s too painful to admit that, then it’s likely you will find a way to connect your childhood to your current job and justify why it’s in your nature to be where you are, even if it actually isn’t. Instead, you want to think as honestly and objectively as you can about your childhood and the activities you did. Once you’ve done that, you can probably link them to certain aspects of your job, or previous jobs you had, that confirm that nature. Even if it’s not the entire job.

Which video games do you/did you play?

Which video games do you play, or did you play when you were younger? What were you drawn towards?

For me, I loved RPG, strategy and base-building games as a kid. Today I don’t game often, but when I do it’s base-building games (I’m specifically drawn towards Factorio, Satisfactory, Dyson Sphere Program. Those games are like crack).

My guess is that what your drawn towards video game-wise has some reflection of your nature. If you’re the person who plays a resource management game like Factorio, and you’ve got excel spreadsheets setup to do all the math in order to optimize the production lines, then you’re either already an engineer, or you have an engineering mindset. It’s probably in your nature to optimize a business or something similar. And if you’re stuck in a role that doesn’t let you exercise your nature, then you’ll likely feel like something’s missing.

If you loved RPG games that had strong storylines, then my hunch is you’re probably more creative.

What feels like play to you but work to others?

Another way to phrase this question is: “What do you find easy but others find hard?”

I was talking to a friend a while back who wanted to start making more content. Writing a newsletter, doing YouTube, etc.

We were talking about the research and writing process—the act of synthesizing disparate information—and he said something like, “Yeah, but man is that hard to do. Takes so much effort.”

I was puzzled. My instant reaction and response was, “It’s hard? I love it. Feels like play to me.”

And after talking with a few other friends who confirmed the same thing, that it is indeed hard for a lot of people, I realized that I’m probably doing the work I should be doing.

What feels like play to you? Maybe you can’t figure that out without asking other people. But which activities get you deep into flow states? What are you doing in your spare time, that feels both productive but also like play?

For me, it’s reading/writing/synthesizing information. I can’t not do it. Doesn’t mean it’s always easy, but it mostly feels like play.

Caveat: sometimes, it doesn’t feel like play at all. It feels like work. We don’t live in sunshine and rainbow land where everything is perfect and frictionless. The point is that the work that comes naturally to you (even if it’s sometimes difficult) is much harder for the majority of other people. That’s the work you should be doing.

Personality tests

You want to treat personality tests as another data point in the constellation of data points from other exercises. They are useful tools to help you understand yourself better. But you shouldn’t let them influence your behaviour in stupid ways.

For example, on the Big Five tests, I score extremely low in agreeableness.

That doesn’t mean I never agree with people, or always act like an asshole and disagree with people and justify my behaviour by saying “Yeah, well it’s just in my nature to be disagreeable. Sorry, that’s how I am. Can’t change it.” Actually, the negative manifestation of your natural traits should be something you aim to control, not let loose. You should master yourself. It’s called self-control.

Personality tests are useful to understand your nature better so you can make better decisions about what you pursue. If you’re very low in openness and creativity, for example, then that probably says something about the type of work you should or shouldn’t do. If you’re low in agreeableness like me, then working a customer service job where you have to deal with angry, irrational customers might be difficult.

Again, it’s one data point. But you may start to notice patterns. For example:

- Your gain and drain list shows that you gain energy from designing and thinking about processes and problems.

- As a child, you were always trying to figure out how to be more efficient at doing your chores (like how you could most efficiently wash the dishes)

- You played resource management and strategy games as a kid.

- When you engage in the type of work that requires this way of operating, it feels like play to you.

- You take a personality test and it shows that you’re high in analytical, low in openness, high in conscientiousness.

In this case, it’s pretty obvious that it’s in your nature to be doing some type of analytical/engineering type work.

Closing thoughts

Leaning into your nature doesn’t mean you live a life of ease

Nothing comes easy.

The 5’8” marathon runner who has the genetic capability and drive to become world-class doesn’t find it easy to become world-class. It’s not a given. And that’s proven by the many people who share such genetics who never try, or don’t put in enough work.

Even when you’re surrendering to your nature, you cannot neglect the importance of self-discipline, work ethic, and strategic decision making. You still should do the work whether you feel like it or not. If it’s in your nature to be a writer, then write. Even on days where you don’t want to, or it feels like it’s not in your nature. It is.

The point is not that leaning into your nature means you live life on easy mode. It’s that leaning into your nature feels right. And right doesn’t always mean easy. But one thing’s for sure, it’s a lot more enjoyable and fulfilling than going against your nature.

Leaning into your nature doesn’t mean surrendering to all your bad traits

You want to embrace the best version of your nature, not the worst version. When you lean into your nature, it doesn’t mean you default to the lazy, procrastinator part of your nature (if that’s a part of you). It means doubling down on your strengths.

Lean into your nature. Do not be a victim of the dark side of your nature.

Leaning into your nature doesn’t mean you stop growing

Leaning into your nature is an act of growth, not regression. It’s anti-stasis. We know this because it’s something that’s extremely difficult to do. It’s painful. It’s uncomfortable.

Leaning into your nature doesn’t mean you stop developing a diverse skillset. It doesn’t mean you avoid becoming a T-Shaped individual. It simply means that you’re operating from a place that aligns with who you really are, instead of who you think you want to be (but really don’t).

You’re accepting that you have certain strengths and weaknesses, and that while some of those weaknesses are worth shoring up, some aren’t. Especially when you consider the opportunity cost of shoring them up versus doubling down on strengths.

—

Thanks for reading. Now go, lean into your nature and do what you were made to do.