What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. —Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death

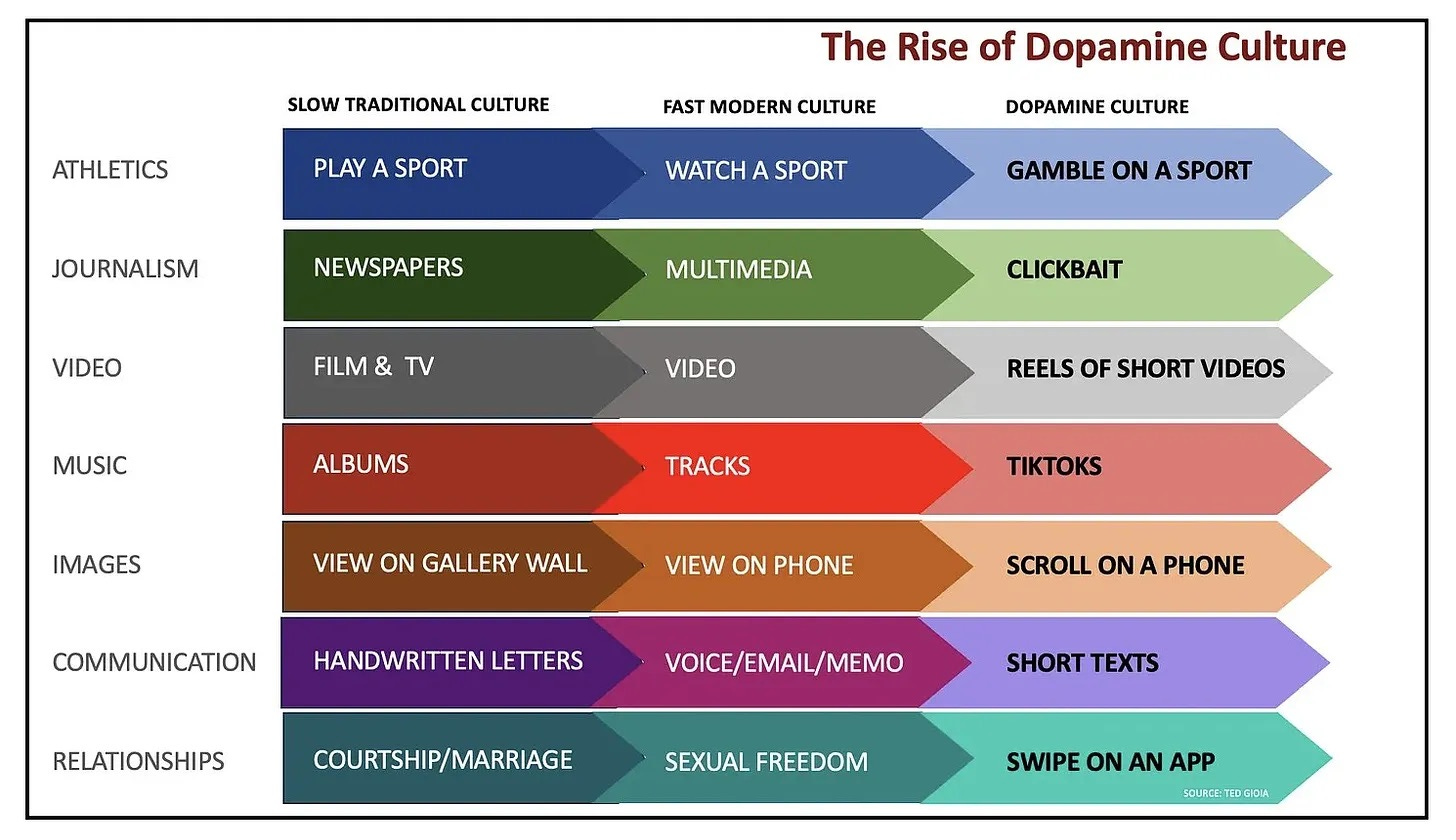

Our world is much closer to Huxley’s vision detailed in Brave New World as opposed to Orwell’s 1984. No one reads books anymore. We are overloaded with information. “Truth” is delivered to us in soundbites and 15 second vertical videos. We live in what Ted Gioia calls Dopamine Culture, a significant shift from the slow traditional culture of past.

This post is an exploration of that shift: how information changed, what dopamine culture is doing to us, who’s behind it, and what the future holds.

I) How The Information Era Bankrupted Our Minds

“To bankrupt a fool, give him information.” — Nassim Taleb

“… the introduction into a culture of a technique such as writing or a clock is not merely an extension of man’s power to bind time but a transformation of his way of thinking—and, of course, of the content of his culture.” —Neil Postman

It’s the year 1400. The introduction of the mechanical clock has begun to dictate daily life. The seeds of industrialism and capitalism are firmly planted and growing. Yet the printing press is still decades away. Information is scarce and travels slowly by horseback.

You find yourself in conversation with a villager. After explaining how you managed to travel back in time 600+ years, they ask what the future looks like. You tell them that soon, the printing press will revolutionize society, helping lead to the reformation, renaissance and age of enlightenment. The church will lose its stranglehold on “truth” as information is decentralized and flows freely.

You introduce them to concepts like capitalism. You share the wonders and pains of the coming industrial revolution—the machine age. You describe how the invention of the telegraph enables information to travel vast distances in an instant instead of taking days or weeks. And that a century later, information will take on the form of moving images inside a box we call the television.

Before you get to the difficult task of trying to explain the internet, smartphone and social media, your new friend might make an assumption: that the radical increase in the quantity and flow of information can only be a good thing. That the telegraph, TV, and anything that follows can only lead to a better society.

In many ways, they’d be right. We no longer need to pay indulgences to the church. We can learn whatever we like, when we like. We can communicate with the global village in real time, all the time.

But this assumption would also be wrong. What the villager doesn’t realize is that when technology allows information to flow faster and increase in volume, meaning and understanding don’t necessarily follow. In fact, it’s quite the opposite: as the medium of communication has shifted, the quality of information and our ability to understand it has degraded.

To understand this, and how it leads to dopamine culture, we need to take a brief look at how technological innovations in media have shaped our minds. I’d like to suggest a variation of Gioia’s three cultures, that over the last 500 or so years, we’ve moved through four “information eras:” The Printed Era, The Instant Era, The Image Era, and now the Dopamine Era (alternative title: the Hyper-Information Era).

With each successive era comes a seismic shift in the culture at large. The technological innovation that drives cultural shift is not merely something that attaches itselfto the skin of society, it forces itself into the bloodstream and changes it from the inside out. It’s ecological, as Neil Postman describes in Technopoly:

Technological change is neither additive nor subtractive. It is ecological … it changes everything. In the year 1500, fifty years after the printing press was invented, we did not have old Europe plus the printing press. We had a different Europe.

The Printed Era—the Age of Reason or the Age of Typography—was a period of significant intellectual output. The written word dominated and shaped culture. It fundamentally changed how we thought about ourselves and the world, leading to the rise of rationalist thought in the West.

Part of the reason for this is that the medium is the message, as Marshall McLuhan taught us. That the way information gets to us is just as important, if not more important than the information itself. The medium of written word shaped culture in particular ways. Neil Postman, again:

“In reading, one’s responses are isolated, one’s intellect thrown back on its own resources. To be confronted by the cold abstractions of printed sentences is to look upon language bare, without the assistance of either beauty or community. Thus, reading is by its nature a serious business. It is also, of course, an essentially rational activity.”

This medium produced a bias toward exposition. A “sophisticated ability to think conceptually, deductively and sequentially.” Postman adds.

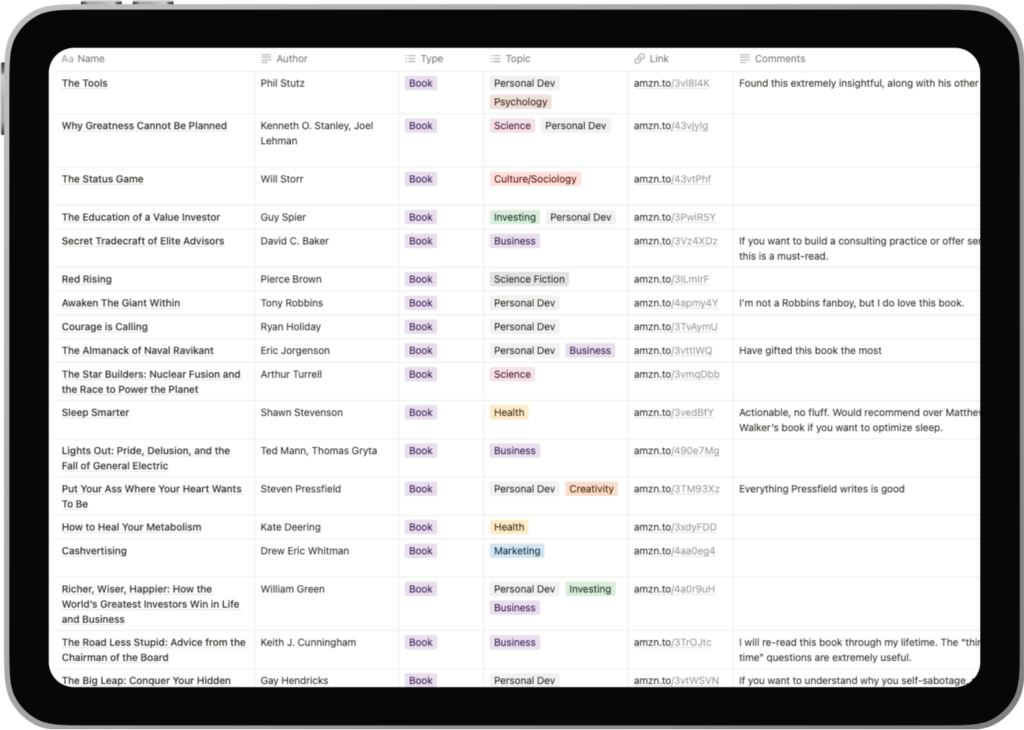

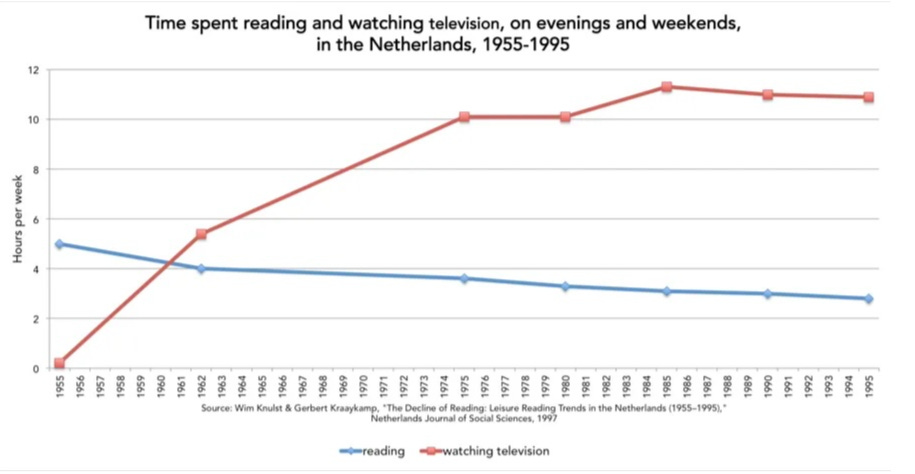

While we have more printed material available today (~4 million books are published each year), it doesn’t hold a monopoly. Like I said, people don’t read anymore. But during the Printed Era, if you wanted to learn something, you read a book. If you wanted to share structured information, writing was how you did it.

This culture of reading and intellectual engagement wasn’t limited to the upper strata of society either. In The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes, Jonathan Rose details the flourishing literary culture among working class Scotland:

Scottish mutual improvement expressed itself chiefly in libraries … John Crawford has located fifty-one Scottish working-class libraries founded by 1822, which charged annual subscriptions of 6s. or less, and were governed democratically, mostly without interference by the middle classes.

And if you’re still not convinced of the dominance of the printed word during this era, consider that Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, published in 1776, sold 100,000 copies in two months. To match that today in proportion to population increase, you’d need to sell 8 million copies in two months—practically unheard of in the realm of non-fiction.

The Printed Era began its decline in 1847 with the invention of the telegraph. The Instant Era had begun. Not “instant” like we think of it today, with unlimited access to limitless movies and TV shows on demand, food delivery, and Amazon Prime. Rather, the delivery of information and communication became, for all practical purposes, instant.

The telegraph was a fantastic invention, but by radically increasing the ease and speed at which information could be communicated, it changed the Information-Action ratio. Prior to the telegraph, most information presented to you was relevant. You didn’t know about the high profile divorce case in Chicago while living in NYC. It wasn’t relevant. If you did find out about it, it was several days or weeks later. Postman explains (emphasis mine):

Prior to the age of telegraphy, the information-action ratio was sufficiently close so that most people had a sense of being able to control some of the contingencies in their lives. What people knew about had action-value. In the information world created by telegraphy, this sense of potency was lost, precisely because the whole world became the context for news. Everything became everyone’s business. For the first time, we were sent information which answered no question we had asked, and which, in any case, did not permit the right of reply.

In the Instant Era, information was something to be consumed more than understood. Context, coherence and nuance were slowly replaced by speed, variety and volume—a trend that has continued. The Instant Era meant being well-informed at the expense of being well-educated.

The invention of the telegraph gave way to radio, and the radio to the television. Culture remained instant, but now had another dimension: image. Television moved us away from a word-centric culture to an image-centric culture. Unlike the Instant Era, the Image Era wasn’t even about being “informed” anymore, it was about entertainment. The news anchors knew this even if the viewer didn’t, as Robert MacNeil, executive editor and co-anchor of the MacNeil-Lehrer Newshour points out:

[The idea] is to keep everything brief, not to strain the attention of anyone but instead to provide constant stimulation through variety, novelty, action, and movement. You are required… to pay attention to no concept, no character, and no problem for more than a few seconds at a time.

Where the reader engages in active consumption, judging the information in front of him, analyzing the text, reading and re-reading at a natural pace… the viewer in the Image Era is passively entertained, stimulated, and oriented around images instead of exposition. Postman writes:

“Americans no longer talk to each other, they entertain each other. They do not exchange ideas; they exchange images. They do not argue with propositions; they argue with good looks, celebrities and commercials.”

Television was the foundation of fast modern culture and dopamine culture. Aside from their algorithmic engines, TikTok and Instagram reels are not that qualitatively different from television. At least, not in the way television is different to written text. It’s an evolution of the medium (video) rather than a step change. And the goal is the same: to hook, entertain, stimulate, and keep you engaged for as long as possible.

Finally, we move to the Dopamine Era. Entertainment on steroids. More variety, infinite content, always on, and even less nuance and context. Not only can you be informed on-demand, you don’t have a choice. In fact, you’ll become addicted to the ceaseless activity. Gioia writes:

The fastest growing sector of the culture economy is distraction. Or call it scrolling or swiping or wasting time or whatever you want. But it’s not art or entertainment, just ceaseless activity.

Not only is it the culture of distraction and addiction, it’s one of shallowness too. In a media world where engagement reigns supreme, understanding and depth are second place—if they’re even considered at all. That’s why you get high school students who watch a 2 minute TikTok video about a complex topic, like climate change or a chaotic geopolitical issue, and think they “get it.” It’s not just high school students, it’s all of us. We don’t go deep anymore. We don’t read. And our collective cognition is dominated by whatever the current thing is. We know more about the last 24 hours than the last 500 years, and it shows.

II) The Dopamine Industrial Complex

The rise of television, just like all innovations, was driven by incentives. Engaging content meant more viewers which meant more advertising revenue. The same incentives have driven tech companies to create dopamine culture, and they aren’t slowing down.

Zuck didn’t wake up one day in his college dorm thinking about how he could get billions of people addicted to scrolling Instagram reels. He set out to build a network for university students. But companies evolve. Users matter. Engagement matters. Time on platform matters. Make those numbers go up and ad revenue follows.

The dopamine industrial complex that Zuck is a part of (probably) isn’t some evil cabal deadset on making everyone passive and addicted. It’s simply a group of people and organizations heavily incentivized to maximize shareholder value at your expense. You don’t pay with your money, you pay for it with your time, your mental health, and perhaps even your soul. It’s a group made up of the generation’s best minds, all getting paid good great money to figure out how to make you more addicted. As one Meta employee wrote in 2021:

“No one wakes up thinking they want to maximize the number of times they open Instagram that day … But that’s exactly what our product teams are trying to do.”

There’s another layer of incentive that makes it worse: each big player in the dopamine industrial complex is vying for market share (or eyeball share). This creates a perverse dynamic where companies must add features to “keep up.” If Meta decides tomorrow—out of the good for humanity—that they’ll make Instagram less engaging, what would happen? Users would flock elsewhere. We’d switch to a more engaging platform, because that’s what we’ve been trained to do. We’d spend more time on TikTok, or YouTube shorts, or whatever new form of digital fentanyl enters the marketplace. Meta’s eyeball share would decline, as would their stock price.

The best example of this is the proliferation of short form video. First Vine, then TikTok, followed by Instagram and now YouTube Shorts. I remember a time where many IG users were glad that there was no shorts product, naively thinking that the platform had maintained its integrity as an image/photo-first platform. But the incentives were too strong to resist. In Why Everything is Becoming a Game, Gurwinder describes this competitive loop in the context of gamification:

“Companies that exploit our gameplaying compulsion will have an edge over those who don’t, so every company that wishes to compete must gamify in ever more addictive ways, even though in the long term this harms everyone. As such, gamification is not just a fad; it’s the fate of a digital capitalist society. Anything that can be turned into a game sooner or later will be. And the games won’t just be confined to our phones — “extended reality” eyewear like Meta Quest and Apple Vision, once they become normalized, will make playing even harder to avoid.”

III) Is there any hope?

It’s hard to be optimistic, and it’s hard to see dopamine culture as merely a trend, as Gioia points out:

This is more than just the hot trend of 2024. It can last forever—because it’s based on body chemistry, not fashion or aesthetics.

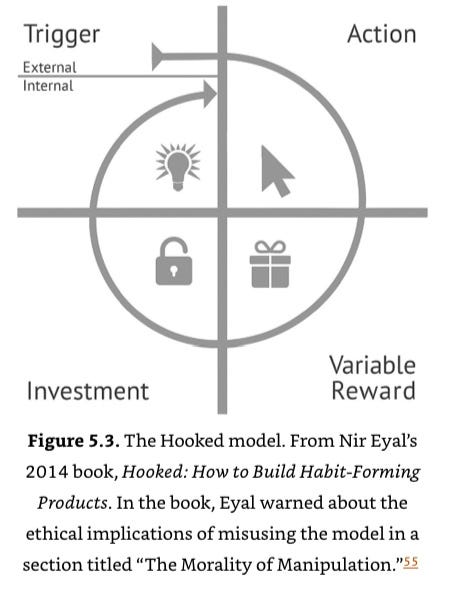

The hijacking of our brain chemistry makes reversal difficult. Our entertainment and media consumption has become drug-like, because it follows this powerful dopaminergic feedback loop:

- Trigger: you’re bored, and you want to feel something, so you grab your phone.

- Action: You open TikTok

- Variable reward: You watch videos and you don’t know what you’re going to see, which makes it exciting. Maybe it’s funny, maybe it’s doomscrolling, maybe it’s lame. But at least it’s something.

- Investment: You keep going. You can’t look away. And you’ll repeat this loop again in an hour or so when you feel its pull.

I speculate that there’s underlying societal factors that drive dopamine culture, beyond the brain hijacking. Millennials and Gen Z are plagued by uncertainty and the anxiety that comes with it. Escapism is a natural response to that. If you’re anxious, you want to distract yourself. And you’re going to do it with something, even if you know it’s not that good for you. We’ll even take pain over uncertainty.

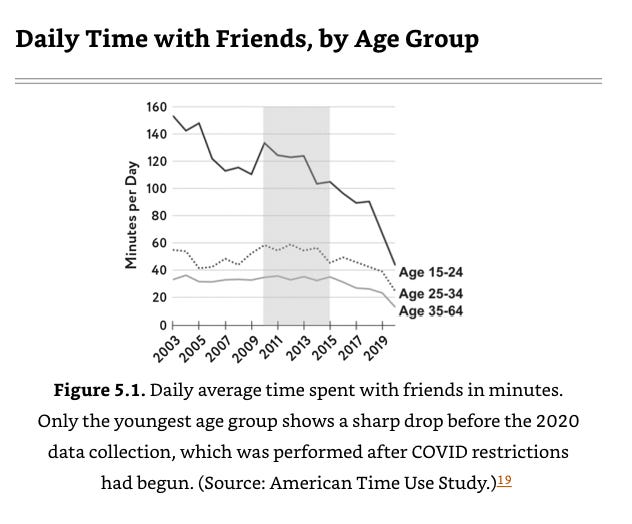

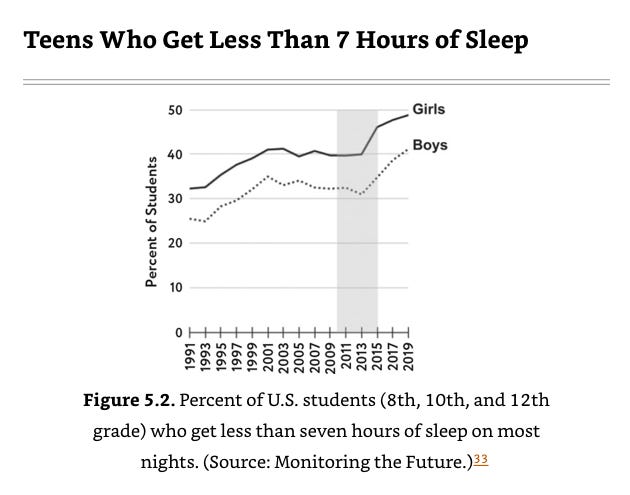

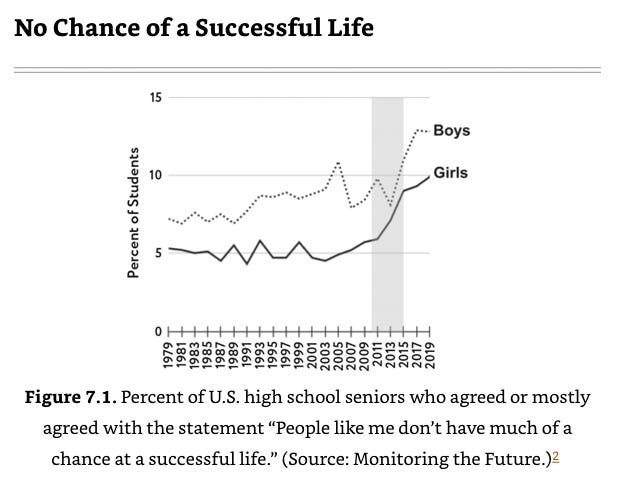

It’s not looking great. Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generationis filled with alarming statistics. Here are a few:

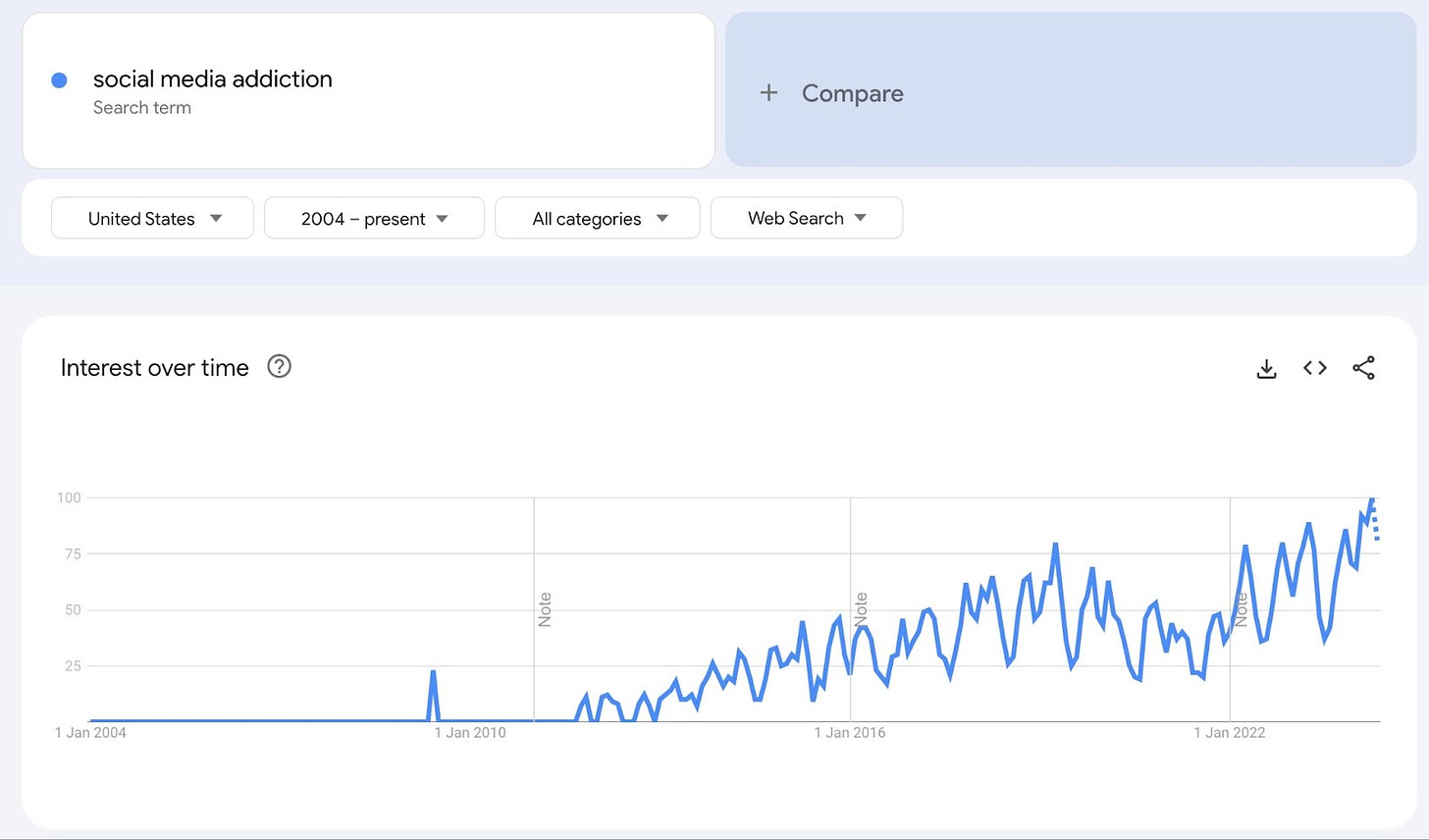

But not all hope is lost. Compared to 10 years ago, we are far more aware of how pervasive this problem is. Not only are we more aware, but we’re taking action. The majority of people I talk to in my age cohort (25-35) have actively built boundaries in their lives to mitigate the negative effects of social media addiction and dopamine culture. They’ve given up their smartphone and chosen to use a dumbphone instead, or they’ve deleted their social media, or they’ve disabled notifications and created rules for themselves like no phone before bed.

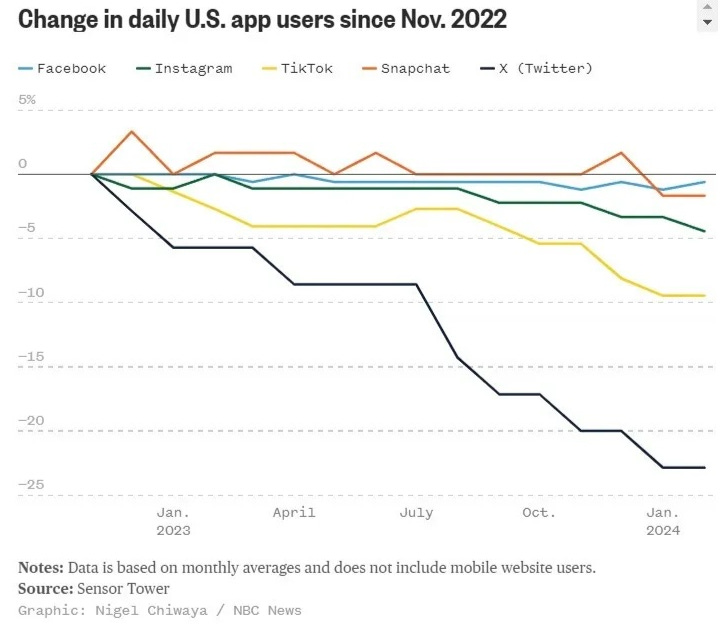

Many social media apps are actually on the decline.

Apps like Opal and Clearspace continue to grow as people have a strong desire to fix their smartphone addiction problems.

And let’s remember: Smoking was extremely addictive, yet the smoking rate among US adults today is 11.5% compared to the 42% it was in 1965. Knowledge of health risks, and the subsequent social disapproval, drove this.

Could the same thing happen with social media? Could the health risks drive collective behavior? Could social disapproval compound and effect change? Hopefully.

I don’t think we’ll ever return to a pre-dopamine culture world. But I do think there’s a growing cohort of people who are opting out of the experiment being run by the dopamine cartel. They’ve had enough. They know it’s bad. And they know that slower, traditional culture provides something that dopamine culture cannot: beauty, depth, richness, coherence, and truth.

IV) What to do about it

“Push back against the age as hard as it pushes against you.” — Flannery O’Connor

Mark Manson suggests that we fight dopamine culture by following an Attention Diet.

“The same way we discovered that the sedentary lifestyles of the 20th century required us to physically exert ourselves and work our bodies into healthy shape, I believe we’re on the cusp of discovering a similar necessity for our minds. We need to consciously limit our own comforts. We need to force our minds to strain themselves, to work hard for their information, to deprive our attention of the constant stimulation that it craves.”

We need to violently reduce the information flowing to us. We need to pay attention to less, just like our ancestors did. As Manson writes:

“In a world with infinite information and opportunity, you don’t grow by knowing or doing more, you grow by the ability to correctly focus on less.”

He offers some directives:

- Apply the law of “F*ck Yes” or No to your social media connections. Prior to dopamine culture, we weren’t friends with anyone and everyone. If they’re affecting your life negatively, you can unfriend them.

- Unfollow all news and media outlets (including sports and entertainment)

- Uninstall any apps that feel pointless

- Choose good sources of information and connection

- Schedule your diversions

- Use website blockers & phone blockers

“The Attention Diet should be emotionally difficult to implement.”

This can’t be understated. The same way exercising and following a nutritional diet is hard, because we’re working against habits and feedback loops we’ve built prior, so should our fight against dopamine culture be. It’s hard. Emotionally. You will have cravings. You will want to quell the anxiety and uncertainty that life throws at you. Take courage and face it.

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” —James Baldwin

Do hard things. Read old books. Delete social media off your phone. Go hiking. Get outside more. Catch up with that friend. Write something. Paint. Build. Craft. Walk and ponder. Do something inefficient on purpose.

Find the thing that you can get obsessed with—that which makes cheap dopamine appear for what it is: cheap dopamine. The more you’re chasing what’s beautiful, good, and true—and the more you are following your curiosity and ambition—the less tempting it is to engage in meaningless, dopamine hijacking activity.

Understand that you, and the culture at large, are being shaped. Take back as much control as you can. Be judicious in your use of technology. Shape yourself.

The villager you meet during the year 1400 might like to time-travel back with you to the 21st century. After all, modern medicine is pretty cool. So is air travel, and cars, and modern infrastructure. But given what you’ve told him about dopamine culture, he’d likely go into it with eyes wide open. We should do the same.

“But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin.” —Aldous Huxley, Brave New World